Winter Warning for Donkey Owners

So, I wish I did not have to start this process again…but unfortunately, I do. Once again I have a senior horse with a variety of acute and chronic conditions that all hit at the same time. Right now I am trying to make her comfortable while also trying to figure out what is what and how to best respond.

Three months ago Tilly was tested for EPM due to muscle wasting and weight loss.The first time she was in the lower end of an active infection. We started a compounded medicine for 1 month and her numbers decreased. We decided to do another round as she responded well to the first round. However, the numbers remained the same. We also tested her for Lyme which showed a chronic and an active infection but the numbers were in the high normal range and the vet felt that it was not treatment worthy at the time.

Last month Tilly began “crab walking” out of the blue. Called the vet. They came out. Her ataxia was bilateral- both her left and right hind- whereas EPM tends to be unilateral. Further, her presentation was not suggestive of Lyme.

We started steroids (dexamethasone oral power) for 5 days with Banamine, tapering as we went, and she seemed to recover. The consensus was it was an acute attack that may have occurred given she is a senior with a history of being an Amish workhorse and perhaps, she pulled something in her neck.

Treatment was complete and another week went by and again, she showed some ataxia. This time less severe. The vet felt that since she responded well to the first round of steroids that it was not EPM-related as you would not see improvement. Further, if it were Lyme related the presentation would be more consistent. Again, a round of Dex and improved quickly. The next week we had her neck x-rayed and there were some arthritic changes. However, she was running around and moving well so the vet felt injections in her neck would not be necessary at that time.

Seventy two hours later, she had some trouble getting up but eventually succeeded. The next morning my sweet girl was spinning, crab walking, and falling over. It was absolutely terrible to see. I immediately gave her 10cc IV Banamine and she calmed down and stopped spinning. The vet came out and administered Dex IV and thought that due to her inflammatory bowel disease we should try Dex IM to ensure absorption. We also decided to pull blood to test for Cushings as she seemed to lose weight overnight and was not shedding out well. The next day she was lame on her right front. Panicked I called the vet fearing that if she did have Cushings, she was trying to founder due to the steroid use. Thankfully, the vet came out, did a nerve block on her right front (this helps to see if the horse has laminitis as they will improve once blocked) and checked for pulses (if a horse has laminitis typically they will have pulses in their hooves) and Tilly did not have any. So, the vet did not feel we were dealing with founder. However, the lameness presented a major challenge due to her still being ataxic on the hind end. The vet did cortisone injections into her neck hoping to help with inflammation due to arthritis. Tilly did great and suddenly, began freaking out. Spinning, knocking into the doors, etc. The vet explained that the injections likely added more pressure on her spinal cord causing her to react. Again, once the vet was able to safely administer Banamine and some Dorm, she calmed and laid down for the first time in over a week for a good 45 minutes. We decided to make sure she was able to get back up. Although she had some trouble, after a couple tries, she was able to do so. Her breathing was heavy, wheezy, almost like she was having a panic attack and hyperventilating. A few minutes later, her breathing returned to normal.

Tilly’s Cushing’s text level was about 100 pg/mL (it should be about 30 pg/mL during mid-November to mid-July) meaning, she does have Cushings. The vet decided to wean her off of the steroid as to not increase the risk of Laminitis even more but also to give neck injections time to work (5-7 days). We also immediately began Prescend (2 tabs) a day to treat her Cushings.

We are on day 5 since the 3rd ataxic episode and day 3 post neck injection and she is still lame on her right front along with ataxic on her hind end. However, she is still eating, engaging, and is bright and alert. She does not seemed distressed or in pain thankfully. Due to Tilly not showing much improvement (even though it can take 5-7 days to see improvements from the neck injections) I decided to start her on a non-compounded EPM medication, Protazil. According to the vet, Protazil should not cause any harm whether her symptoms are EMP related or not. I also began 10cc of Vitamin E oil. Tilly was previously on pelleted Vitamin E but due to her inflammatory bowel disorder, she may struggle to absorb the pelleted form of the supplement. Further, there are a number of studies showing the benefits of Vitamin E and the connection between Vitamin E and ataxia.

On a positive note, since starting Prescend for her Cushings, I have noticed that she is drinking less water. Increased water intake is a symptom of unmanaged Cushings. I am hopeful that means the medication has started to work at regulating her hormones. We are now at a wait and see point. I continue to try to make her comfortable. Tons of bedding in her huge foaling stall, hay everywhere, fans on, doors open. She has been a trooper. My hope is that she recovers from this and enjoy whatever time she has left and fights this as she has so many other things- the reason she was given the name, Ottilie.

RESOURCES

https://www.horseillustrated.com/horse-health-equine-cushings-disease-24321

https://www.horseillustrated.com/horse-experts-horse-vet-advice-cushings-disease-diet

https://cvm.msu.edu/vdl/laboratory-sections/endocrinology/equine-endocrine-testing

https://www.horseillustrated.com/horse-experts-horse-vet-advice-cushings-horse-treats

https://resources.integricare.ca/blog/cushings-disease-in-horses

The most common esophageal conditions in horses is choking and it is always an emergency.

Typically, there is a cause to this condition like eating too quickly, food being too dry or suck together, or even a lack of water. Some horses may choke due to their dental health as well. Further, abnormal esophagus anatomy can also contribute a predisposition to choking, Food may form a firm bolus that becomes lodged in their esophagus. However, other items can also cause an obstruction like hay or straw, hard treats, carrots, and even, nonfood objects.

How to tell if your horse is choking?

What to do when you suspect your horse is choking?

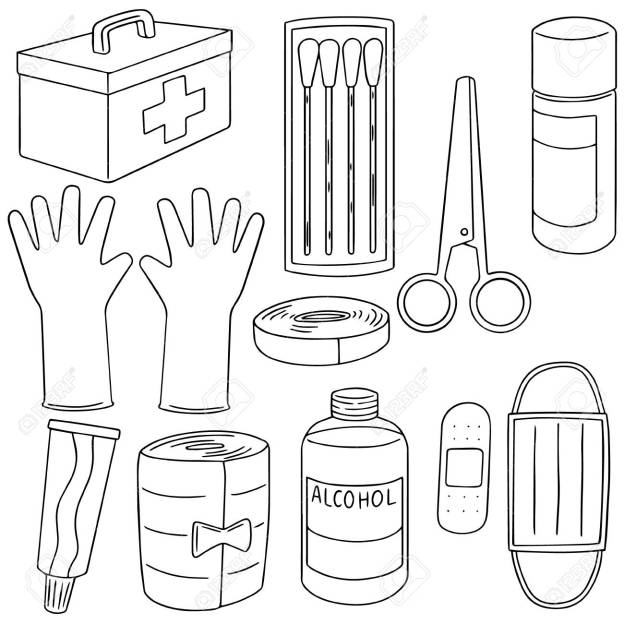

Equine First Aid Kit

All horse owners should have an equine first aid kit & know how to use all of the supplies. At least twice yearly, examine & replenish outdated supplies. Store your first aid kit in your home or temperature controlled space. Leaving it in a trailer or uninsulated tack room will quickly degrade the supplies. Talk to your veterinarian about customizing your first-aid kit for your horse’s particular needs.

FUNDAMENTALS

Thermometer, Mercury or Digital

Stethoscope (good quality)

Headlight (good quality)

Proper Fitting Halter & Lead Rope

Latex Gloves (12)

Watch or Timepiece with Second Hand

BASIC EQUIPMENT

Bandage Scissors

Suture Scissors

Tweezers or Forceps (smooth jaws)

Non-Sterile Gauze – 4″x4″ Squares (1 package)

Conform® or Kling® Gauze 4″ (2 rolls)

Elastic Adhesive Bandage (Elasticon®) 3″ (2 rolls)

Cohesive Bandage (Vetrap®) 4″ (2 rolls)

Non-Adhesive Wound Dressing (Telfa® pads) 3″x4″ (2) & 3″x8″ (2)

Povidone Iodine (Betadine®) Solution (4 oz)

Antiseptic Scrub, Chlorhexidine or Povidone Iodine (Betadine®) Scrub (4 oz)

Sugardine

Small Plastic Containers for Mixing or Storage (2)

Wound Lavage or Cleaning Bottle, Saline (250 ml)

Tongue Depressors (6)

Alcohol Wipes (10)

Spray Bottle for Water (1)

Paper Towels (1 roll)

Multi-Purpose Tool, Leatherman® or Equivalent

Cotton Lead Rope (3/4″ – 1″ in diameter)

Electrolytes (paste or powder)

Fly Repellent Ointment (1)

Heavy Plastic Bags (2 – gallon & 2 – pint size)

SECONDARY EQUIPMENT

Cotton, Rolled Sheets, Leg Cottons (2)

Standing Wrap & Quilt or Shipping Boots

Easy Boot or Equivalent in Appropriate Size

Baby Diapers (2) (size 4 to 6 depending on hoof size)

Triple Antibiotic Ointment (1 tube)

Extra Halter & Lead Rope

Lariat

Syringe 35 cc (1)

Syringe 12cc (3)

Syringe 3 cc (3)

Syringe 3cc with 20gauge needle (3)

Syringe – 60 cc cath tip (2)

Needles – 18gauge – x 1.5″ (4)

Needles – 20 gauge – x1.5″ (4)

Eye Wash, Saline (1 bottle)

Opthalmic Ointment or Drops (1 bottle or tube)

Magnesium Sulfate, Epsom Salts (1 package)

Duct Tape (1 roll)

Clippers with #40 Blade (good quality)

Shoe Puller

Crease Nail Puller

Hoof Pick

Hoof Knife

Hoof File, Rasp

Clinch Cutters

Farrier’s Driving Hammer

Collapsible Water Bucket

Ice Wraps

Twitch

Bute Banamine Bordered

Talk to your veterinarian about dispensing a few medicines that you may use in an emergency. In most, if not all states, a veterinarian cannot legally dispense prescription items without a valid Veterinary Client Patient Relationship (VCPR).

• Flunixin Meglumine (Banamine®) (injectable or paste)

• Phenylbutazone, Bute Paste (1)

• Trimethoprim-Sulfa Tablets SMZ-TMP in small container (75#)

Learn equine biosecurity basics for the farm, horse show, and breeding shed to protect your horses from infectious diseases.

— Read on thehorse.com/features/practical-biosecurity-tips-to-protect-your-horse/

#1 Abdominal Pain, Colic Signs Perform Whole Horse Exam™ (WHE) Assess Color of Mucous Membranes Assess Demeanor or Attitude Assess Gut or Intestinal Sounds Assess Manure Assess Capillary Refill Time (CRT) by examining Gums Give Intramuscular (IM) Injection Give Oral Medication Sand Sediment Test…

— Read on horsesidevetguide.com/Common+Horse+Emergencies+and+the+Skills+You+Need+to+Help

With freezing temperatures comes the need for extra care and attention for horses and other equids.

The growing season some parts of the nation had last year produced overly stemmy or fibrous hay with a lower digestibility. As a result, making certain that horses are supplemented with grain when fed lower quality hay will help them maintain body weight and condition, a key factor in withstanding cold temperatures.

Constant access to clean, fresh water at 35 to 50°F is an absolute necessity to keeping horses healthy. This can be achieved via heated tanks or buckets, or by filling a tank, letting it freeze, cutting an access hole in the frozen surface, and then always filling the tank to below the level of the hole from that point on. This provides a self-insulating function and will typically keep the water below from freezing. Regardless of the method you choose, it’s important to check tanks frequently to ensure your horse’s water remains free of ice.

Additional ways to keep horses comfortable in cold weather include making sure they have access to shelter. A well-bedded, three-sided shed facing south or east will typically provide adequate protection from wind and snow, as can appropriate bluffs or treed areas.

When the temperatures get colder, mature horses will not typically move around much in an effort to conserve energy. Making an attempt to keep hay, shelter, and water fairly close together can limit the energy expenditure required, thus conserving body condition.

And, finally, keeping horses at a body condition score of 5 or 6 (on a 9-point scale) will help prevent surprises when horses shed their winter hair in the spring, and improve conception rates for those choosing to breed.

More so than from other tragedies, I find myself physically as well as emotionally affected by these stories. As the horses usually have absolutely no chance of escaping, I think it is probably the horse owner’s worst nightmare.

Emotions aside, in my job as a professional electrician, I am mindful that many of these fires are caused by faulty electrical wiring or fixtures. Over the year,s I have borne witness to my share of potential and actual hazards. Designing a barn’s electrical system to today’s codes and standards is a topic for another day. For today, let’s address what we can do to make the existing horse barn safer.

I can’t cite statistics or studies, but my own experience shows the main safety issues that I am exposed to fall into three general categories:

The first item I am addressing is extension cords.

I am often asked how extension cords can be UL-listed and sold if they are inherently unsafe. The answer is that cords are not unsafe when used as intended, but become so when used in place of permanent wiring.

The main concern is that most general purpose outlets in barns are powered by 15 or 20 ampere circuits, using 14 or 12 gauge building wiring, respectively. Most cords, however, for reasons of economy and flexibility, are rated for 8 or 10 amperes, and are constructed of 18 or 16 gauge wiring. That’s no problem if you are using the cord as intended—say, powering a clipper that only draws 1 to 4 amperes.

The problem comes when the cord is left in place, maybe tacked up on the rafters for the sake of “neatness.” You use it occasionally, but then winter comes and you plug a couple of bucket heaters into it. When the horses start drinking more water because it’s not ice cold, two buckets become four—or more.

If they draw 2.5 amperes each, you are now drawing 10 amperes on your 18 gauge extension cord that is only rated to carry 8 amperes. The circuit breaker won’t trip because it is protecting the building wiring, which is rated at 20 amperes. A GFCI outlet won’t trip either because the problem is an overload, not a ground fault.

Anyway, next winter, you decide to remove two of the buckets and add a trough outside the stall with a 1500 watt heater, which draws 12.5 amps at 120 volts. If you thought of it, you even replaced the old 18 gauge cord with a 16 gauge one that the package called “heavy duty.” Now the load is 17.5 amperes on a cord that is designed to handle 10 amperes.

In this case, it is possible to overload a “heavy duty” cord by using it at 175% of its rated capacity and never trip a circuit breaker. What has happened is, we’ve begun to think of the extension cord as permanent wiring, rather than as a temporary convenience to extend the appliance cord over to the outlet.

In doing so, we have created an unsafe condition.

Overloaded cords run hot. Heat is the product of too much current flowing over too small a wire. The material they are made of isn’t intended to stand up over time as permanent wiring must. It’s assumed that you will have the opportunity to inspect it as you unroll it before each use.

The second item on our list is exposed lamps (bulbs) in lighting fixtures.

Put simply, they don’t belong in a horse barn. A hot light bulb that gets covered in dust or cobwebs is a hazard. A bulb that explodes due to accumulating moisture, being struck by horse or human, or simply a manufacturing defect introduces the additional risk of a hot filament falling onto a flammable fuel source such as hay or dry shavings.

In the case of an unguarded fluorescent fixture, birds frequently build nests in or above these fixtures due to the heat generated by the ballast transformers within them. Ballasts do burn out, and a fuel source—such as that from birds’ nesting materials—will provide, with oxygen, all the necessary components for a fire that may quickly spread to dry wood framing.

The relatively easy fix is to use totally enclosed, gasketed and guarded light fixtures everywhere in the barn. They are known in the trade as vaporproof fixtures and are completely enclosed so that nothing can enter them, nothing can touch the hot lamp, and no hot parts or gases can escape in the event of failure.

The incandescent versions have a cast metal wiring box, a Pyrex globe covering the lamp, and a cast metal guard over the globe. In the case of the fluorescent fixture, the normal metal fixture pan is surrounded by a sealed fiberglass enclosure with a gasketed lexan cover over the lamps sealed with a gasket and secured in place with multiple pressure clamps.

The last item, overloaded branch circuits, is not typically a problem if the wiring was professionally installed and not subsequently tampered with. If too much load is placed on a circuit that has been properly protected, the result will be only the inconvenience of a tripped circuit breaker.

The problem comes when some “resourceful” individual does a quick fix by installing a larger circuit breaker. The immediate problem, tripping of a circuit breaker, is solved, but the much more serious problem of wiring that is no longer protected at the level for which it was designed, is created.

Any time a wire is allowed to carry more current than it was designed to, there is nothing to stop it from heating up to a level above which is considered acceptable.

Unsafe conditions tend to creep up on us—we don’t set out to create hazardous conditions for our horses.

Some may think it silly that the electrical requirements in horse barns (which are covered by their own separate part of the National Electric Code) are in many ways more stringent than those in our homes.

I believe that it makes perfect sense. The environmental conditions in a horse barn are much more severe than the normal wiring methods found in the home can handle. Most importantly, a human can usually sense and react to the warning signals of a smoke alarm, the smell of smoke, or of burning building materials and take appropriate action to protect or evacuate the occupants. Our horses, however, depend on us for that, so we need to use extra-safe practices to keep them secure.

As I always state in closing my electrical safety discussions, I know that we all love our animals. Sometimes in the interest of expedience, we can inadvertently cause conditions that we never intended. Electrical safety is just another aspect of stable management. I often use the words of George Morris to summarize:

“Love means giving something our attention, which means taking care of that which we love. We call this stable management.”

Thomas Gumbrecht began riding at age 45 and eventually was a competitor in lower level eventing and jumpers. Now a small farm owner, he spends his time working with his APHA eventer DannyBoy, his OTTB mare Lola, training her for a second career, and teaching his grandson about the joy of horses. He enjoys writing to share some of life’s breakthroughs toward which his horses have guided him.

I walked outside to sit on my porch and enjoy the evening, when I realized that the time is fast approaching where I can not longer do so without bundling up first. I decided it was time to get ready for the winter months ahead especially for my equine friends.

I have included articles, lists, resources, etc to help you make sure you and your horse are ready for the dropping temperatures!

By: Dr. Lydia Gray

Hot chocolate, mittens and roaring fires keep us warm on cold winter nights. But what about horses? What can you do to help them through the bitter cold, driving wind and icy snow? Below are tips to help you and your horse not only survive but thrive during yet another frosty season.

Your number one responsibility to your horse during winter is to make sure he receives enough quality feedstuffs to maintain his weight and enough drinkable water to maintain his hydration. Forage, or hay, should make up the largest portion of his diet, 1 – 2 % of his body weight per day. Because horses burn calories to stay warm, fortified grain can be added to the diet to keep him at a body condition score of 5 on a scale of 1 (emaciated) to 9 (obese). If your horse is an easy keeper, will not be worked hard, or should not have grain for medical reasons, then a ration balancer or complete multi-vitamin/mineral supplement is a better choice than grain. Increasing the amount of hay fed is the best way to keep weight on horses during the winter, as the fermentation process generates internal heat.

Research performed at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine showed that if during cold weather horses have only warm water available, they will drink a greater volume per day than if they have only icy cold water available. But if they have a choice between warm and icy water simultaneously, they drink almost exclusively from the icy and drink less volume than if they have only warm water available. The take home message is this: you can increase your horse’s water consumption by only providing warm water. This can be accomplished either by using any number of bucket or tank heaters or by adding hot water twice daily with feeding. Another method to encourage your horse to drink more in winter (or any time of the year) is to topdress his feed with electrolytes.

It may be tempting to give your horse some “down-time” during winter, but studies have found that muscular strength, cardiovascular fitness and overall flexibility significantly decrease even if daily turnout is provided. And as horses grow older, it takes longer and becomes more difficult each spring to return them to their previous level of work. Unfortunately, exercising your horse when it’s cold and slippery or frozen can be challenging.

First, work with your farrier to determine if your horse has the best traction with no shoes, regular shoes, shoes with borium added, shoes with “snowball” pads, or some other arrangement. Do your best to lunge, ride or drive in outside areas that are not slippery. Indoor arenas can become quite dusty in winter so ask if a binding agent can be added to hold water and try to water (and drag) as frequently as the temperature will permit. Warm up and cool down with care. A good rule of thumb is to spend twice as much time at these aspects of the workout than you do when the weather is warm. And make sure your horse is cool and dry before turning him back outside or blanketing.

A frequently asked question is: does my horse need a blanket? In general, horses with an adequate hair coat, in good flesh and with access to shelter probably do not need blanketed. However, horses that have been clipped, recently transported to a cold climate, or are thin or sick may need the additional warmth and protection of outerwear.

Horses begin to grow their longer, thicker winter coats in July, shedding the shorter, thinner summer coats in October. The summer coat begins growing in January with March being prime shedding season. This cycle is based on day length—the winter coat is stimulated by decreasing daylight, the summer coat is stimulated by increasing daylight. Owners can inhibit a horse’s coat primarily through providing artificial daylight in the fall but also by clothing their horse as the temperature begins to fall. If the horse’s exercise routine in the winter causes him to sweat and the long hair hampers the drying and cooling down process, body clipping may be necessary. Blanketing is then a must.

Health

There are a number of health conditions that seem to be made worse by the winter environment. The risk of impaction colic may be decreased by stimulating your horse to drink more water either by providing warm water as the only source or feeding electrolytes. More time spent inside barns and stalls can exacerbate respiratory conditions like “heaves” (now called recurrent airway obstruction), GI conditions like ulcers, and musculoskeletal conditions like degenerative joint disease. Control these problems with appropriate management—such as increasing ventilation in the barn and increasing turnout time—and veterinary intervention in the form of medications and supplements.

Freeze/thaw cycles and muddy or wet conditions can lead to thrush in the hooves and “scratches,” or, pastern dermatitis, on the legs. Your best protection against these diseases is keeping the horse in as clean and dry surroundings as possible, picking his feet frequently, and keeping the lower limbs trimmed of hair. Another common winter skin condition is “rain rot,” caused by the organism Dermatophilus congolensis. Regular grooming and daily observation can usually prevent this problem, but consult your veterinarian if your horse’s back and rump develop painful, crusty lumps that turn into scabs.

Winter Resources

Preparing your horse and barn for winter

Winter Nutrition Tips for Horses

Penn State: Winter Care for Your Horses