|

|

|

|

|

|

Tonight I lost my best friend, Chance. The one who whinnied the moment my car pulled up, would run away and wait for me to catch him only to turn around and run away again. He made me laugh, knew all my secrets and nuzzled me when I was sad. He taught me about unconditional love and having a positive attitude despite circumstances. He nodded when I asked if he loved me and gave kisses to get treats. He’s the 17.1 hand horse who would stand behind me and fall asleep as I did my school work and would get upset if any horse got near me but would never hurt a fly. He let children hug him and dogs run into his stall and let me dress him up with flowers. He loved rolling in the snow, laying in the sunshine, and would light up the moment he saw me. I’ll miss playing in the barn on cold nights and curling up reading in his stall when he wasn’t feeling well. I’m thankful that he waited for me to get there tonight to say goodbye so I could hold his head in my lap and talk to him while he passed. There will never be a sweeter horse with a more gentle and pure soul. Thank you, Bubba, for being with me through it all- high school, college, the break ups, the losses, the good and bad days. You gave one hell of a fight for 30+ years. Lucky and I will miss you- there will never be another you❤️ #myfavoriteredhead #chancewetake #20yearstogether #thebesthorseintheworld #myheart

More so than from other tragedies, I find myself physically as well as emotionally affected by these stories. As the horses usually have absolutely no chance of escaping, I think it is probably the horse owner’s worst nightmare.

Emotions aside, in my job as a professional electrician, I am mindful that many of these fires are caused by faulty electrical wiring or fixtures. Over the year,s I have borne witness to my share of potential and actual hazards. Designing a barn’s electrical system to today’s codes and standards is a topic for another day. For today, let’s address what we can do to make the existing horse barn safer.

I can’t cite statistics or studies, but my own experience shows the main safety issues that I am exposed to fall into three general categories:

The first item I am addressing is extension cords.

I am often asked how extension cords can be UL-listed and sold if they are inherently unsafe. The answer is that cords are not unsafe when used as intended, but become so when used in place of permanent wiring.

The main concern is that most general purpose outlets in barns are powered by 15 or 20 ampere circuits, using 14 or 12 gauge building wiring, respectively. Most cords, however, for reasons of economy and flexibility, are rated for 8 or 10 amperes, and are constructed of 18 or 16 gauge wiring. That’s no problem if you are using the cord as intended—say, powering a clipper that only draws 1 to 4 amperes.

The problem comes when the cord is left in place, maybe tacked up on the rafters for the sake of “neatness.” You use it occasionally, but then winter comes and you plug a couple of bucket heaters into it. When the horses start drinking more water because it’s not ice cold, two buckets become four—or more.

If they draw 2.5 amperes each, you are now drawing 10 amperes on your 18 gauge extension cord that is only rated to carry 8 amperes. The circuit breaker won’t trip because it is protecting the building wiring, which is rated at 20 amperes. A GFCI outlet won’t trip either because the problem is an overload, not a ground fault.

Anyway, next winter, you decide to remove two of the buckets and add a trough outside the stall with a 1500 watt heater, which draws 12.5 amps at 120 volts. If you thought of it, you even replaced the old 18 gauge cord with a 16 gauge one that the package called “heavy duty.” Now the load is 17.5 amperes on a cord that is designed to handle 10 amperes.

In this case, it is possible to overload a “heavy duty” cord by using it at 175% of its rated capacity and never trip a circuit breaker. What has happened is, we’ve begun to think of the extension cord as permanent wiring, rather than as a temporary convenience to extend the appliance cord over to the outlet.

In doing so, we have created an unsafe condition.

Overloaded cords run hot. Heat is the product of too much current flowing over too small a wire. The material they are made of isn’t intended to stand up over time as permanent wiring must. It’s assumed that you will have the opportunity to inspect it as you unroll it before each use.

The second item on our list is exposed lamps (bulbs) in lighting fixtures.

Put simply, they don’t belong in a horse barn. A hot light bulb that gets covered in dust or cobwebs is a hazard. A bulb that explodes due to accumulating moisture, being struck by horse or human, or simply a manufacturing defect introduces the additional risk of a hot filament falling onto a flammable fuel source such as hay or dry shavings.

In the case of an unguarded fluorescent fixture, birds frequently build nests in or above these fixtures due to the heat generated by the ballast transformers within them. Ballasts do burn out, and a fuel source—such as that from birds’ nesting materials—will provide, with oxygen, all the necessary components for a fire that may quickly spread to dry wood framing.

The relatively easy fix is to use totally enclosed, gasketed and guarded light fixtures everywhere in the barn. They are known in the trade as vaporproof fixtures and are completely enclosed so that nothing can enter them, nothing can touch the hot lamp, and no hot parts or gases can escape in the event of failure.

The incandescent versions have a cast metal wiring box, a Pyrex globe covering the lamp, and a cast metal guard over the globe. In the case of the fluorescent fixture, the normal metal fixture pan is surrounded by a sealed fiberglass enclosure with a gasketed lexan cover over the lamps sealed with a gasket and secured in place with multiple pressure clamps.

The last item, overloaded branch circuits, is not typically a problem if the wiring was professionally installed and not subsequently tampered with. If too much load is placed on a circuit that has been properly protected, the result will be only the inconvenience of a tripped circuit breaker.

The problem comes when some “resourceful” individual does a quick fix by installing a larger circuit breaker. The immediate problem, tripping of a circuit breaker, is solved, but the much more serious problem of wiring that is no longer protected at the level for which it was designed, is created.

Any time a wire is allowed to carry more current than it was designed to, there is nothing to stop it from heating up to a level above which is considered acceptable.

Unsafe conditions tend to creep up on us—we don’t set out to create hazardous conditions for our horses.

Some may think it silly that the electrical requirements in horse barns (which are covered by their own separate part of the National Electric Code) are in many ways more stringent than those in our homes.

I believe that it makes perfect sense. The environmental conditions in a horse barn are much more severe than the normal wiring methods found in the home can handle. Most importantly, a human can usually sense and react to the warning signals of a smoke alarm, the smell of smoke, or of burning building materials and take appropriate action to protect or evacuate the occupants. Our horses, however, depend on us for that, so we need to use extra-safe practices to keep them secure.

As I always state in closing my electrical safety discussions, I know that we all love our animals. Sometimes in the interest of expedience, we can inadvertently cause conditions that we never intended. Electrical safety is just another aspect of stable management. I often use the words of George Morris to summarize:

“Love means giving something our attention, which means taking care of that which we love. We call this stable management.”

Thomas Gumbrecht began riding at age 45 and eventually was a competitor in lower level eventing and jumpers. Now a small farm owner, he spends his time working with his APHA eventer DannyBoy, his OTTB mare Lola, training her for a second career, and teaching his grandson about the joy of horses. He enjoys writing to share some of life’s breakthroughs toward which his horses have guided him.

Researchers are testing an endoscopic camera, contained in a small capsule and placed directly into the horse’s stomach, to gather imagery of the equine intestinal tract. The capsule sends images to an external recorder, held in place by a harness.

Courtesy, Western College of Veterinary Medicine

Traditionally, veterinarians’ and researchers’ view of the equine intestinal tract has been limited. Endoscopy (inserting through the horse’s mouth a small camera attached to a flexible cable to view his insides) allows them to see only as far as the stomach. While ultrasound can sometimes provide a bigger picture, the technology can’t see through gas—and the horse’s hindgut (colon) is a highly gassy environment.

These limitations make it hard to diagnose certain internal issues and also present research challenges. But the view is now expanding, thanks to a “camera pill” being tested by a team at the University of Saskatchewan, led by Julia Montgomery, DVM, PhD, DACVIM. Dr. Montgomery worked with a multi-disciplinary group, including equine surgeon Joe Bracamonte, DVM, DVSc, DACVS, DECVS, electrical and computer engineer Khan Wahid, PhD, PEng, SMIEEE, a specialist in health informatics and imaging; veterinary undergraduate student Louisa Belgrave and engineering graduate student Shahed Khan Mohammed.

In human medicine, so-called camera pills are an accepted technology for gathering imagery of the intestinal tract. The device is basically an endoscopic camera inside a small capsule (about the size and shape of a vitamin pill). The capsule, which is clear on one end, also contains a light source and an antenna to send images to an external recording device.

The team thought: Why not try it for veterinary medicine?

They conducted a one-horse trial using off-the-shelf capsule endoscopy technology. They applied sensors to shaved patches on the horse’s abdomen, and used a harness to hold the recorder. They employed a stomach tube to send the capsule directly to the horse’s stomach, where it began a roughly eight-hour journey through the small intestine.

The results are promising. The camera was able to capture nearly continuous footage of the intestinal tract with just a few gaps where the sensors apparently lost contact with the camera. For veterinarians, this could become a powerful diagnostic aid for troubles such as inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. It could provide insight on how well internal surgical sites are healing. It may also help researchers understand normal small-intestine function and let them see the effect of drugs on the equine bowel.

The team did identify some challenges in using a technology designed for humans. They realized that a revamp of the sensor array could help accommodate the horse’s larger size and help pinpoint the exact location of the camera at any given time. That larger size also could allow for a larger capsule, which in turn could carry more equipment—such as a double camera to ensure forward-facing footage even if the capsule flips.

With this successful trial run, the team plans additional testing on different horses. Ultimately, they hope to use the information they gather to seek funding for development of an equine-specific camera pill.

“From the engineering side, we can now look at good data,” Dr. Wahid explained. “Once we know more about the requirements, we can make it really customizable, a pill specific to the horse.”

This article was originally published in Practical Horseman’s October 2016 issue.

Your horse comes in from being outside and is barely able to move. His legs are swollen, he has a fever, is sensitive to the touch, and has a loss of appetite. He has chills- intermittently shaking. He wont touch his hay, his eyes are dull, and he looks depressed and tired. You call the vet and they run hundreds of dollars worth of tests- CBC, x-ray his legs to ensure there is no fracture; they diagnose him with Lymphingitis. You begin a course of antibiotics. You cold hose. You give him Banamine. Your wrap his legs while he is on stall rest. A week later, the swelling has subsided, his fever has dissipated, and his appetite is back.

You get a text saying that your horse “ran away” when he had been let out earlier that day. But when you get to the barn, you notice when he turns he looks like his hind end is falling out from under him..remember when you were little and someone would kick into the back of your knees and your legs would buckle? That is what it looks like. So you watch him. You are holding your breath, hoping he is just weak from stall rest. You decide, based on the vet’s recommendation, to let him stay outside for the evening. You take extra measures- leaving his stall open, with the light on, wrapping his legs, etc- and go home. Every time your mind goes to “what if..”, you reassure yourself that your horse is going to be okay and that you’re following the vet’s advice and after all, your horse had been running around earlier that day.

The next morning your horse comes inside and it takes him an hour to walk from the paddock to his stall. All four legs are swollen. He has a fever (101.5). He is covered in sweat. He won’t touch his food. He has scrapes all over his body and looks like he fell. You call the vet- again- and they come out to look at him. They note his back sensitivity, his fever, the swelling at his joints (especially the front). They note that his Lymphingitis seems to have come back. The vet draws blood to check for Lyme. They start him on SMZs and Prevacox. You once again wrap his legs, ice his joints, give him a sponge bath with alcohol and cool water to bring down his fever. You brush him, change his water, put extra fans directed at his stall. You put down extra shavings. And you watch him.

A few days go by and you get a call saying that your horse has tested positive for Lyme…and while your heart sinks, you are also relieved that there is an explanation for your horse’s recent symptoms. You plan to begin antibiotics and pretty much not breathe for the next 30+ days while your horse is pumped with antibiotics. You pray that he doesn’t colic. You pray that you have caught Lymes in time. You pray that the damage is reversible. You research everything you can on the disease. And you sit and wait….

Below are resources on Lyme Disease in horses- treatments, symptoms, the course of the disease, and the prognosis.

Lyme Disease in Horses | TheHorse.com

Lyme Disease, testing and treatment considerations | Best Horse Practices

Microsoft Word – Lyme Multiplex testing for horses at Cornell_2-12-14 –

Today Chance had swelling of his back right fetlock. He had a fever around 104 and didn’t eat his feed. His eyes were dull and he was lethargic. He wasn’t limping but was walking slower than normal (he usually runs to the paddock or back to the barn). I decided, due to the Lymphingitis flare up on his back right leg, I would give him a shot of 5 mls (or 5 cc) of Banamine and wrap his leg. Once the medication set in, I would bring him in to give him a bath (it was 80 degrees today). So, that is what I did. By the time he was back at the barn he was covered in sweat. I cold hosed him and drenched the wrap in cool water and let him roam around the barn.

Thankfully, the vet was able to meet me at her veterinary practice so that I could pick up Baytril and more Banamine. Since Chance just had Lyme Disease (and had finished his medication less than a week ago), we are not 100% if this is a Lyme reaction or something else. The plan is to administer 25 cc of Baytril either orally, in his feed, or via IV for 6 days and Banamine 10 mls (or a 1000 lbs) twice a day for 3 days. The vet suggested that I do 5 cc of Banamine if his fever remains between 101-103 degrees and 10 cc if his fever is 103 degrees or above. During this time I will begin Prevacox- one 1/4 of a tablet once a day. After 3 days, I will discontinue the Banamine and continue the Prevacox. If his fevers are not down in two days, I will continue the Baytril but start the doxycycline as it maybe a Lyme disease symptom.

While researching Lyme Disease, I found that many people do two+ months of doxycycline instead of 30 days to ensure the disease has been erraticated completely. However, since Chance had shown such improvement after 30 days, I decided to not do another month. Maybe I should have…

However, Chance had similar symptoms when we found a small laceration in the DDFT tendon of his back left hind- swelling, Lymphingitis, fever, lethargy, no appetite, etc. If he does have an issue with his tendon I will most likely do another round of Stem Cell treatments which proved to be helpful last time. Thankfully I stored his stem cells in a Stem Cell Bank (via Vet-Stem) and can easily have them shipped.

True North Equine Vets www.truenorthequinevets.com 540-364-9111

Genesis Farriers: Dave Giza www.genesisfarriers.com 571-921-5822

Ken Pankow www.horsedentistvirginia.com 540-675-3815

Full Circle Equine www.fullcircleequine.com 540-937-1754

Farriers Depot: (Farrier related supplies) www.farriersdepot.com 352-840-0106

StemVet (Stem cell acquisition and storage) www.vet-stem.com

SmartPak Equine Supplements www.smartpakequine.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

I walked outside to sit on my porch and enjoy the evening, when I realized that the time is fast approaching where I can not longer do so without bundling up first. I decided it was time to get ready for the winter months ahead especially for my equine friends.

I have included articles, lists, resources, etc to help you make sure you and your horse are ready for the dropping temperatures!

By: Dr. Lydia Gray

Hot chocolate, mittens and roaring fires keep us warm on cold winter nights. But what about horses? What can you do to help them through the bitter cold, driving wind and icy snow? Below are tips to help you and your horse not only survive but thrive during yet another frosty season.

Your number one responsibility to your horse during winter is to make sure he receives enough quality feedstuffs to maintain his weight and enough drinkable water to maintain his hydration. Forage, or hay, should make up the largest portion of his diet, 1 – 2 % of his body weight per day. Because horses burn calories to stay warm, fortified grain can be added to the diet to keep him at a body condition score of 5 on a scale of 1 (emaciated) to 9 (obese). If your horse is an easy keeper, will not be worked hard, or should not have grain for medical reasons, then a ration balancer or complete multi-vitamin/mineral supplement is a better choice than grain. Increasing the amount of hay fed is the best way to keep weight on horses during the winter, as the fermentation process generates internal heat.

Research performed at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine showed that if during cold weather horses have only warm water available, they will drink a greater volume per day than if they have only icy cold water available. But if they have a choice between warm and icy water simultaneously, they drink almost exclusively from the icy and drink less volume than if they have only warm water available. The take home message is this: you can increase your horse’s water consumption by only providing warm water. This can be accomplished either by using any number of bucket or tank heaters or by adding hot water twice daily with feeding. Another method to encourage your horse to drink more in winter (or any time of the year) is to topdress his feed with electrolytes.

It may be tempting to give your horse some “down-time” during winter, but studies have found that muscular strength, cardiovascular fitness and overall flexibility significantly decrease even if daily turnout is provided. And as horses grow older, it takes longer and becomes more difficult each spring to return them to their previous level of work. Unfortunately, exercising your horse when it’s cold and slippery or frozen can be challenging.

First, work with your farrier to determine if your horse has the best traction with no shoes, regular shoes, shoes with borium added, shoes with “snowball” pads, or some other arrangement. Do your best to lunge, ride or drive in outside areas that are not slippery. Indoor arenas can become quite dusty in winter so ask if a binding agent can be added to hold water and try to water (and drag) as frequently as the temperature will permit. Warm up and cool down with care. A good rule of thumb is to spend twice as much time at these aspects of the workout than you do when the weather is warm. And make sure your horse is cool and dry before turning him back outside or blanketing.

A frequently asked question is: does my horse need a blanket? In general, horses with an adequate hair coat, in good flesh and with access to shelter probably do not need blanketed. However, horses that have been clipped, recently transported to a cold climate, or are thin or sick may need the additional warmth and protection of outerwear.

Horses begin to grow their longer, thicker winter coats in July, shedding the shorter, thinner summer coats in October. The summer coat begins growing in January with March being prime shedding season. This cycle is based on day length—the winter coat is stimulated by decreasing daylight, the summer coat is stimulated by increasing daylight. Owners can inhibit a horse’s coat primarily through providing artificial daylight in the fall but also by clothing their horse as the temperature begins to fall. If the horse’s exercise routine in the winter causes him to sweat and the long hair hampers the drying and cooling down process, body clipping may be necessary. Blanketing is then a must.

Health

There are a number of health conditions that seem to be made worse by the winter environment. The risk of impaction colic may be decreased by stimulating your horse to drink more water either by providing warm water as the only source or feeding electrolytes. More time spent inside barns and stalls can exacerbate respiratory conditions like “heaves” (now called recurrent airway obstruction), GI conditions like ulcers, and musculoskeletal conditions like degenerative joint disease. Control these problems with appropriate management—such as increasing ventilation in the barn and increasing turnout time—and veterinary intervention in the form of medications and supplements.

Freeze/thaw cycles and muddy or wet conditions can lead to thrush in the hooves and “scratches,” or, pastern dermatitis, on the legs. Your best protection against these diseases is keeping the horse in as clean and dry surroundings as possible, picking his feet frequently, and keeping the lower limbs trimmed of hair. Another common winter skin condition is “rain rot,” caused by the organism Dermatophilus congolensis. Regular grooming and daily observation can usually prevent this problem, but consult your veterinarian if your horse’s back and rump develop painful, crusty lumps that turn into scabs.

Winter Resources

Preparing your horse and barn for winter

Winter Nutrition Tips for Horses

Penn State: Winter Care for Your Horses

We all know the too-familiar story used in crime shows on television. A dynamic duo, perfectly paired in every way. They’re best friends who bicker like an old married couple and complete each other’s lives. That partnership is something most people long for. And it’s something a few equestrians are lucky enough to find with their four-legged half.

I was one of those few. His name was Beau. He was an off-the-track thoroughbred with a heart of gold and the chest of a draft horse. Tall, dark, handsome, loyal, always in tune with my thoughts—he was the best partner a girl could ask for.

We spent hours, days, weeks, months, training together. Athletically, we were on point. Emotionally, we were more in tune than most married couples. In every way, he was my other half. My confidence stemmed from him, and vice versa. There was nothing we couldn’t do when we were together. We literally climbed mountains.

Then, too soon, Beau passed away.

It was sudden. Unexpected. One day he was there, the next I had to make the decision to have him euthanized at the age of seven. That day I lost not only my partner, but a part of myself.

Saying goodbye to a partner is hard. For a while, there’s a hole. It never really gets filled. You keep riding, keep hopping up in that worn-out leather saddle that still smells like him. But it’s never the same. That same passion, love and commitment you shared for one another will never be replaced.

That’s a hard thing to get over. But it’s something every single equestrian will one day have to face. I hope none of you need to face it so soon. I hope your partners grow to be old and gray and pass in the most dignified and peaceful sense. I hope you have time to sit on the ground with them, no matter how hard it may be, hold their head in your lap for the last time and say goodbye.

I hope you get the chance to tell them thank you for the heart they gave you. For the confidence, experience, and love they shared with you every time you stepped into their world. But most of all, I hope you appreciate every single ride.

Go out to your barn and hug your horse.

Let them have that extra snack. Next time they decide they aren’t going to listen, or kick up their heels because they feel fresh, laugh it off. Someday you’ll miss it. You’ll miss the green stains on your white shirt from their grassy kisses. You’re going to miss braiding that mane until your arms ache. You’ll miss hitting the dirt because you couldn’t quite sit their power over that jump. Enjoy every moment of your partnership.

For those who have experienced this and said goodbye, I feel your pain. Don’t be afraid of feeling it, too. Sometimes it’s good to sit down and look at all those old photos and have a good cry over the life you had with your best friend. It’s okay for it to hurt a little bit every time you walk in the barn and they aren’t there waiting for you.

Just remember, they gave the best years of their life to you. They loved you with every ounce of their being. And you returned the favor.

Megan Stephens is small-town equestrian from the hills of New York. She first hit the saddle at the age of four and the obsession has grown ever since. She is mom to a Hackney gelding and competes in hunter/jumper divisions for a local farm. She enjoys freelance writing about her favorite topic in her spare time.

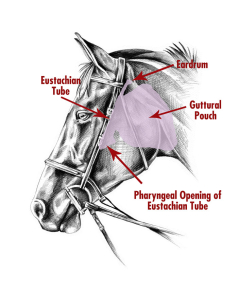

An interesting article I came across about Guttural pouches in horses. Must read for those who work with or around horses.

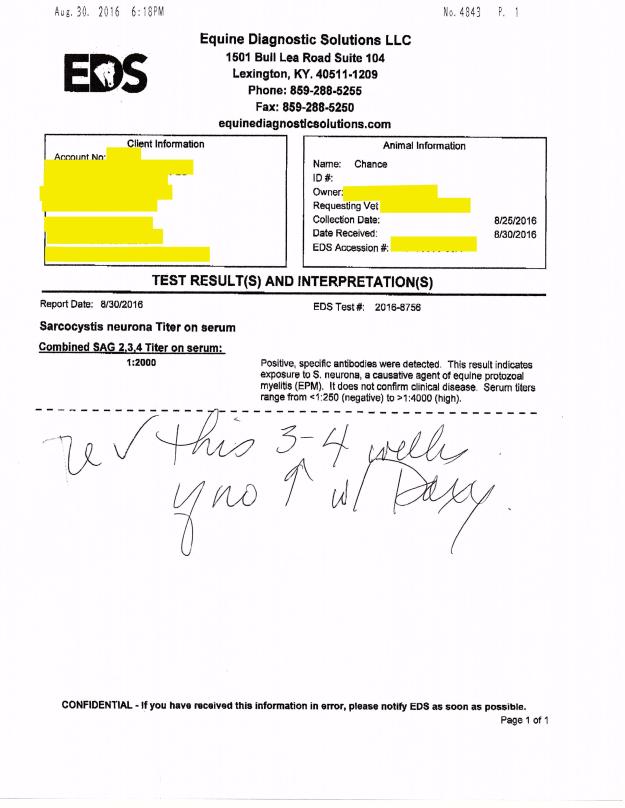

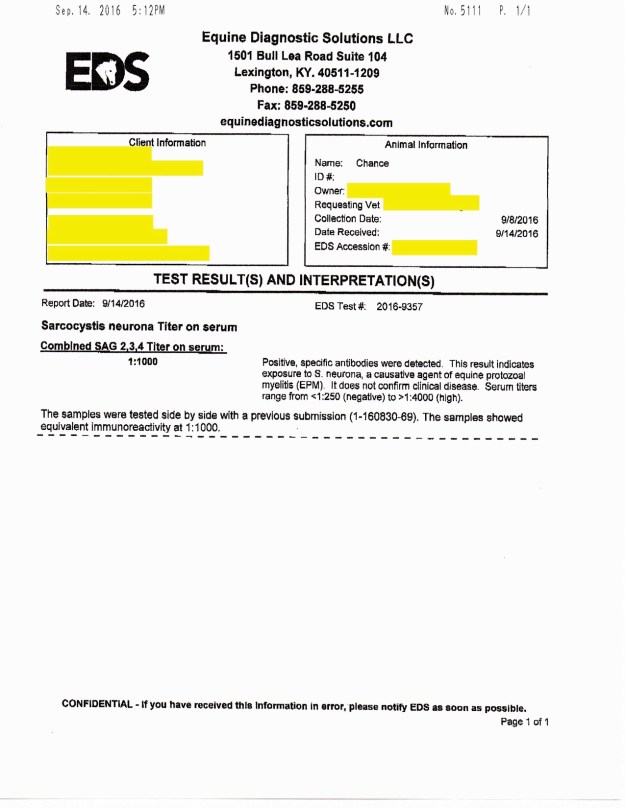

During my horse’s recent Lymphingitis flare-up, the vet advised that we run labs to test for Lyme and EPM due to his presenting symptoms (hind weakness, twisting his back leg at the walk/walking sideways I refer to it as- “Chance’s swagger”). As I noted previously, Chance’s Lyme test revealed that he was at the beginning stages of an acute infection…yay for the labs at Cornell University for their amazing ability to give you more than a positive or negative!

A little history before getting to the EPM Tilter results.

About 2ish years ago, Chance was diagnosed with EPM (and one of the reasons opossums and I are not friends since they host the disease as do a few other culprits). Chance immediately began EPM treatment- he received Protazil in his feed for one month. After hours of research I chose Protazil, although extremely expensive (if you order from http://www.drfosterandsmith.com they sometimes have promotions where you receive store credit for every $100.00 you spend…they did when I ordered and I got a “free” dog bed that my dogs adore), due to the decreased likelihood of Chance experiencing a “Treatment Crisis” (worsening of symptoms) and the ease of administration (other brands require the drug being administered 1 hour before eating or an hour after and so on). Typically, EPM treatment is done for 30 days and, depending on the residual symptoms, some may require subsequent treatments. While Chance’s symptoms improved, I wanted to ensure that we annihilated the disease and did another round of treatment but this time with Marquis. At the end of two months, Chance’s ataxia was gone!

Fast forward to September 2016…Chance, just having a Lymphingitis flare-up, has been tested for Lyme and EPM. Lyme came back positive. And….so did the EPM test..well, kind of. Wonderful. (See why I loathe opossums?)

Chance’s EPM test #2 on 8/30/16 (the 1st one was 2ish years ago) showed the following:

“Combined SAG 2,3,4 Tilter on serum= 1:2000”

So, what does this mean?

The test revealed that Chance had “positive, specific antibodies” detected in the blood work. This means that he had EXPOSURE to S. Neurona, a causative agent of EPM. Serum tilters range from <1:250 (negative) to >1:4000 (high positive). S. Neurona (SarcoFluor) is one of two protozoa found in EPM infected horses, the other protazoa is N. Hughesil (NeoFluor). S. Neurona is most frequently seen, whereas N. Hughesil is not as common.

The vet ran another EPM test to confirm the findings in the 8/30/16 test. The results showed that Chance had “Combined SAG 2,3,4 Tilter on serum= 1:1000. Again, Chance showed EPM protozoa in the positive-ish range.

I initially had not seen the results but was told by the vet that he was EPM negative. So when I asked for the test results to be emailed to me and saw the numbers I sort of freaked out…I emailed the vet to ask for clarification. She explained,

“The EPM test shows that he was exposed to the organism in the first test we did which is why we did a follow-up test. Since his exposure level dropped from 1:2000 to 1:1000 this shows that he does not have the disease. There is no good one time test for EPM once they are exposed which is why we had to do the repeat to compare the two.”

While this explanation offered me comfort, I was confused…why does he have any protozoa in his blood if he doesn’t have EPM?

I spoke to another vet and she explained it in a bit more detail…I am hoping I am summarizing what she said correctly..

When a horse tests positive for EPM they either have an active disease or they may not. However, when the test does from 1:2000 down to 1:1000 this typically means that the horse’s immune system is working correctly to fight the disease off- active or not. EPM testing typically provides you with a % of the chance your horse has an active EPM infection, or at least if you send it to Cornell University. For instance, lets say a horse gets the results back and it shows that they are “positive” or have been exposed to S. Neurona (one of the two EPM protozoa)…their results are 1:647. This means that, after doing a bunch of adding and multiplying that this vet kindly did for me, the horse has a 60-70% chance of having ACTIVE EPM. Meaning, he most likely would be symptomatic (ie: behavioral changes, ataxia, weight loss, difficulty eating, changes in soundness, and a bunch of other neurological symptoms).

My hunch is that Chance’s immune system was boosted because I started him on Transfer Factor (amazing stuff… more information can be found in some of my older posts) again as soon as his results came back positive for Lyme.

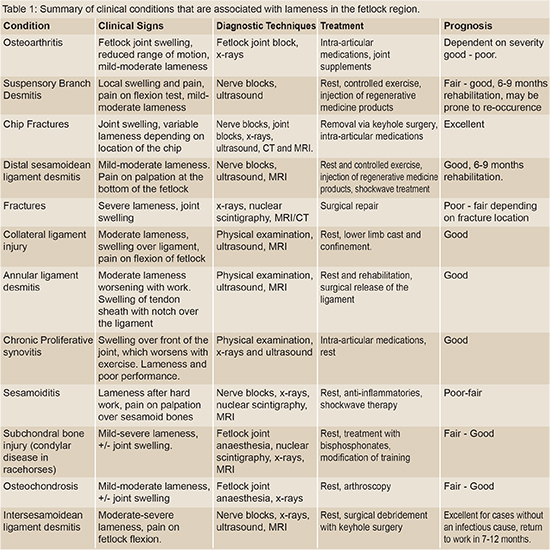

Resources on how to diagnose, treat, prevent, and handle lameness in horses

Your Horse Has a Swollen Leg – Why and What To Do | EquiMed – Horse Health Matters

Fetlock Lameness – It’s importance… | The Horse Magazine – Australia’s Leading Equestrian Magazine

Causes of Equine Lameness | EquiMed – Horse Health Matters

Common Causes of Lameness in the Fetlock