I had the vet run some blood work on Luck and Chance as a precaution, because of the “Panic Grass” in Virginia has been causing liver failure in horses, and because I like to do a full work up every 6-12 months.

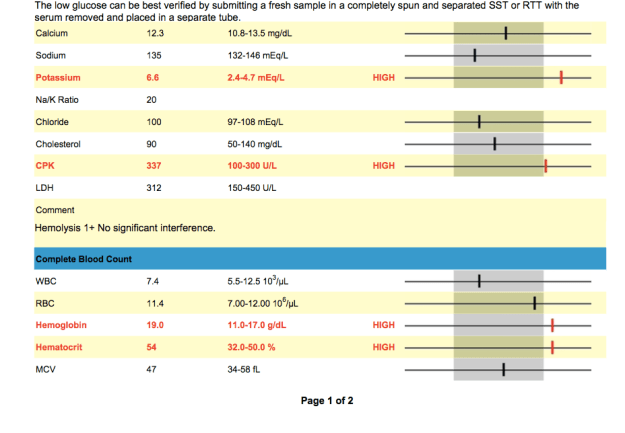

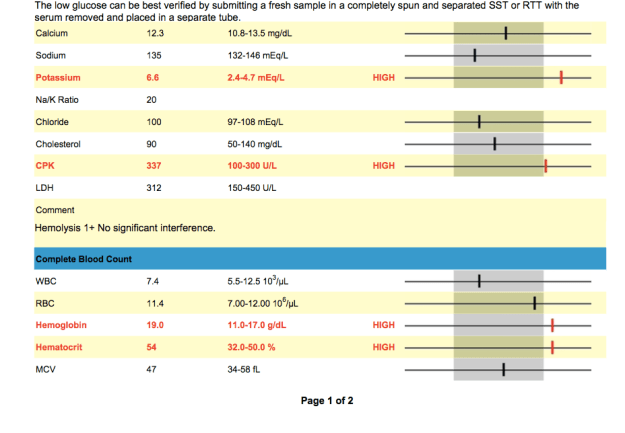

Chance’s Blood Work

INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS

Elevated Potassium (6.6 mEq/L):

“Low levels indicate depletion and are often a predisposing factor, along with

dehydration, in fatigue, muscle cramps, colic, synchronous diaphragmatic flutter (“th

umps”), diarrhea and other symptoms of exhausted horse syndrome. Even seemingly normal or high-normal levels may in reality be lower, but appear higher due to concentration secondary to dehydration as measured by total protein and albumin levels.

Low Sodium:

“Low levels commonly indicate loss through excessive sweating, or through kidney or intestinal disease. Low levels may also be found in young foals with bladder damage. Increased sodium levels are usually a sign of dehydration” (http://www.minstervets.co.uk).

Low Platelets:

This was the most worrisome in regards to the potential immediate issues that could ensue because of the low platelet count.

“The platelets are the third cellular component of blood (along with red and

white blood cells). These cells contain a number of biologically active molecules that are

critical to the blood clotting process. Low levels may indicate a number of disease

processes not necessarily directly related to a bleeding disorder. Chronic or acute blood

loss, immune disease, toxemia, liver, spleen or bone marrow disease, or even critically

reduced or increased body temperatures can also cause low platelets counts. Any

significantly low platelet counts should be further investigated by a veterinarian. High

levels are generally clinically insignificant unless the condition persists, in which case it may be indicative of bone marrow neoplastic disease” (Susan Garlinghouse).

Low Glucose:

“Glucose is the source of the body’s energy. It is measured in suspected cases of equine metabolic syndrome and sometimes in cases of equine Cushing’s disease. Blood glucose may also be measured as part of a glucose tolerance test, assessing small intestinal function” (http://www.minstervets.co.uk).

Chance was tested for Cushing’s Disease within the last year and the test showed that he did NOT have Cushings.

Elevated CPK (337 U/L):

Levels 2-3x the highest number in range are considered significant according to vetstream.com. Levels are easily increased due to poor handling techniques as well as lab error.

According to Dr. Christine Woodford and Carla Baumgartner on vipsvet.com, “Elevations of CPK and SGOT are indictors of muscle inflammation–tying-up or rhabdomyolysis. The term “rhabdo” means muscle and “myolysis” means rupture of muscle cells. The CPK and SGOT are very sensitive indicators of skeletal muscle damage, and they rise in concentration proportionally with the amount of damage. A bit of timing is required in order to obtain the most sensitive results; CPK rises (due to its leakage from muscle cells into the blood system) approximately six to eight hours after the onset of muscle inflammation, and SGOT rises after approximately 12-14 hours. The absolute peak of CPK concentration and the time it takes to return to normal are important indicators of the severity of muscle damage and the response to therapy.”

Elevated MCV: Is the average volume of red blood cells.

- Macrocytosis.

- Indicates immature RBC in circulation (suggests regenerative anemia).

- Very rare in the horse, but may observe increasing MCV within normal range as horses increase erythropoiesis.

According to Vetstream.com, “Macrocytosis (increased MCV) resulting from release of immature RBC from the bone marrow during regeneration is very rare in the horse therefore the MCV is less useful in the horse than in other species.”

Elevated MCH: Is the average amount of hemoglobin in an individual red blood cell.

- Hemolysis, if intravascular in nature .

- Errors can occur during processing

Low RBC:

“You may be inclined to think that red blood cell levels need to drop significantly before they cause a problem for your horse. But the truth is that even low-grade anemia – levels hovering around that 30% range on a PCV – can impact your horse physically and may indicate a health problem. This is especially true for high performance athletes. The greater your horse’s physical condition and demand, the higher on the range of normal her red blood cell counts will typically be. Therefore, a red blood cell level low on the normal range or just below may indicate a concern for a racehorse, for example, where it wouldn’t for that pasture pet.” See more at: http://www.succeed-equine.com/succeed-blog/2014/02/05/anemia-horses-part-1-just-equine-anemia/#sthash.JJuWN5ob.dpuf

Luck’s blood work

Elevated Potassium: Potassium can become elevated for a number of reasons.

According to Vetstream.com,

- 98% of potassium is intracellular.

- Changes in serum or plasma potassium levels reflect fluid balance, rate of renal excretion and changes in balance between intra- and extracellular fluid.

- Hypokalemia increases membrane potential, resulting in hyperpolarization with weakness or paralysis.

- Hyperkalemia decreases membrane potential with resulting hyperexcitability.

Susan Garlinghouse states that, “High serum levels of potassium during an endurance ride are generally not a concern. These increases often reflect nothing more serious than a delay between blood collection (when potassium is actively sequestered inside cells) and sample measurement (after potassium has had time to “leak” from inside the cells out into the plasma or serum).” This could also be a result of Luck and Chance running around in the heat when the vet arrived.

Increased [potassium] (hyperkalemia) can occur from;

- Results can be false due to processing time (ie: if the lab waited too long to process blood sample)

- Immediately after high intensity exercise.

- In association with clinical signs in horses with hyperkalemic periodic paraysis (HYPP) .

- Bladder rupture (neonate) .

- Hypoadrenocorticism [Pituitary: adenoma] (rare).

- Metabolic acidosis.

- Acute renal failure .

- Extensive tissue damage (especially muscle).

- IV potassium salts, eg potassium benzyl penicillin, potassium chloride .

- Phacochromocytoma (rare in the horse).

Hypokalemia

- Chronic diarrhea.

- Diuretic therapy, especially potassium-losing diuretics.

- Excess bicarbonate/lactate therapy.

- Chronic liver disease .

- Acute renal failure (polyuric phase) .

- Recovery from severe trauma.

- Metabolic/respiratory alkalosis.

- Prolonged anorexia.

- Recovery period after high intensity exercise (30-60 min after).

- Parenteral feeding.

In combination with clinical signs and results of other tests results could signify the following;

Elevated GGTP:

* Donkeys tend to have 3x higher levels then horses. This means that in stead of the typical equine range being 1-35 U/L a typically donkey’s range would be up to ~105 U/L. Lucky’s test showed he had 120 U/L which is still elevated but not much. It took sometime to get Luck from the field when the vet arrived- he ran around non stop. The excitement and anxiety could be the cause of the elevated levels.

RBC:

Katherine Wilson, DVM, DACVIM, of the Virginia–Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine (See more at: http://equusmagazine.com/article/decode-horses-bloodwork-27122#sthash.sc4J1ISJ.dpuf) explains “RBC count is probably the least helpful information because horses usually don’t have big changes in red blood cell numbers. It is not uncommon for horses to have an RBC count a little lower than normal range, however. The term we use for low RBC is anemia, but unless the count gets very low, a horse doesn’t necessarily need to be treated for that condition. A lot of diseases or any chronic long-term disease can cause mild anemia. Usually if we see mild anemia on the bloodwork and the horse has other issues, the anemia is just an indication that we need to fix/treat another problem.”

Low or Elevated Values

- Splenic contraction.

- Polycythemia (rare) .

- Dehydration.

- Consider causes of anemia

- Blood loss .

- Hemolysis (i in vivo or artifact).

- Decreased bone marrow production.

- Poor technique at sampling.

- Poor handling and storage of samples.

- Poor technique in laboratory.

Low Bilirubin:

Heather Smith Thomas of Equus states, “Another indication of liver health is a pigment called bilirubin, which is formed from the breakdown of red blood cells. Elevated levels can mean unusual loss of red cells or liver dysfunction. However, in horses, unlike other animals, elevated levels of bilirubin often isn’t serious. “This value can increase fairly rapidly when horses go off feed, and this is something that is unique to the horse,” says Wilson. “Often we get phone calls from veterinarians who don’t work on horses much or owners who see the blood work and note that the bilirubin is above normal range and are concerned about liver disease. If the horse is off feed for 24 to 48 hours, that value will increase, but this is just a temporary elevation.”

Elevated Hemoglobin (19 g/dL):

According to vetstream.com, Thoroughbred and other “hot-blooded” horses Hemoglobin range differs from other equine- the thoroughbred range = 11.0-19.0g/l.

Elevated Hematocrit (54 %):

Elevated levels could be due to;

- Dehydration.

- Splenic contraction.

- Polycythemia .

“A measurement of the relative amount of red blood cells present in a blood

sample. After blood is drawn, a small tube is filled and centrifuged to separate the heavier

blood cells from the lighter white blood cells and the even lighter fluid (plasma or serum)

portion. A higher than normal reading generally indicates dehydration (same number of

cells in less plasma volume) or may be due to splenic contraction secondary to

excitement or the demands of exercise. A low reading may indicate anemia, though not

invariably. Highly fit athletic horses may normally have a slightly lower hematocrit at

rest due to an overall more efficient cardiovascular system. Evaluation of true anemia in

horses requires several blood samples over a 24-hour period” (Susan Garlinghouse, 2000/ http://www.equinedoc.com/PrideProjectInfo.html).

It took sometime to get Luck from the field when the vet arrived- he ran around non stop. The excitement and anxiety could be the cause of the elevated levels.

Low Sodium:

According to horseprerace.com, “Low levels indicate depletion and are often a predisposing factor, along with dehydration, in fatigue, muscle cramps, colic, synchronous diaphragmatic flutter (“thumps”), diarrhea and other symptoms of exhausted horse syndrome. Even seemingly normal or high-normal levels may in reality be lower, but appear higher due to concentration secondary to dehydration as measured by total protein and albumin levels. Therefore, levels at the lower end of the normal range should be evaluated relative to concurrent dehydration.”

More information on your horse’s blood work

Decoding your horse’s blood work

CBC and Chemistry Profile

A Better Understanding of the Results

The vet suggested that I add water to Luck’s and C’s feed in case their values are due to dehydration. She also explained that some of the values may be a result of running around in the field right before drawing them along with anxiety.

The anxiety and running around seemed fair but I am hesitant on the dehydration portion. Yes, I know it is winter and that horses are less likely to drink as much water. But if it were due to dehydration then the Albumin would be low as well. But, the blood work revealed that the Albumin was 2.8 (Luck) and 3.2 (Chance). These values are within the normal range…. that being said, the results could also be due to lab handling especially the Potassium levels.

While speaking with my uncle Jerry (the horse whisperer), he suggested adding a salt block to the horse’s feed. This will increase the horse’s thirst which will get them drinking more. I also added heated water buckets so that the water won’t freeze and in case they are less inclined to drink when the water is cold.

In order to feel comfortable about my horse and donkey being healthy, I will have more blood work done this week to make sure everything is in fact okay.