Sweet Vera was acting lethargic one evening. She did not show any obvious signs of colic like pawing or distress. However, she was laying down more than typical. Whenever approached she would stand up. The most obvious sign was that when she was offered a treat she was not interested. I took her temperature and it was normal. Gut sounds were present but she looked bloated. I decided to give the vet a call. The vet came and tubed her and gave her some banamine. When Vera was tubed, but due to her small stature, a smaller tube had to be used and not much came out.

The next day she continued to act off. Again, I called the vet and decided to bring her into the hospital. There the vet tubed her at intervals throughout the day and into the next. They gave her fluids via an IV and did a few ultrasounds . Thankfully they were able to get a larger tube in her and the thick, paste like substance started coming out…more and more and more. The interesting part of this was that she does not get grain. There was no sand in the substance that was removed from her belly but my guess is someone gave her treats and due to the extreme heat she was not drinking as much- basically, a perfect storm hit.

Day three she began to perk up, have bowel movements, and even started eating some mash. The next day she was able to return home and has been doing well.

How to Spot Colic in Donkeys?

- Dullness

- Lying down

- Lack of appetite or refusing to eat

- Weight shifting, usually between the hind legs

- Rolling and pawing at the ground (rare in donkeys, can indicate a serious problem)

- Fast breathing, rapid heart rate

- Sweating

- Brick red or pale gums or insides of eyelids

- Dry or tacky gums

- Lack of, or reduction in, the normal quantity of droppings

- Self-isolating or moving away from companions.

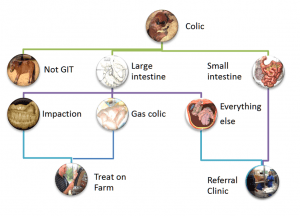

Types of Colic:

Impaction Colic: Impaction occurs when forage, sand, dirt or other material gets lodged in the colon, causing the horse to be unable to pass manure and putting a halt to the whole digestive system. Impaction can also be caused in some cases by enteroliths, naturally occurring mineral deposits that can reach up to 15 pounds in size. Impaction colic tends to occur more in the winter months, due to a lack of hydration.

Gas Colic: Gas colic is a mild, abdominal pain stemming from the result of gas buildup in the horse. This can be caused by a change in diet, low roughage consumption, parasites or administration of wormer.

Sand Colic: Sand colic is caused by the abnormal consumption of large amounts of sand while grazing or eating off dry, sandy ground. Upward of 80 pounds of sand have been found in a colicking horse’s gut. Naturally, sand colic is more common in southern regions where the ground tends to be more mineralized. One way you can help prevent sand colic is to avoid feeding horses from the ground, and instead use a feed pan, bucket or feeder.

Entrapment (or Displacement) Colic: Displacement transpires when the large colon moves to an abnormal location, often occurring at the pelvic flexure, an area where the colon narrows and makes a sharp turn. In some cases, displacement can also lead to entrapment, where something traps the gut and can cut off blood supply.

Enteritis: Abdominal pain can also be caused by enteritis, the general inflammation of the gut. This inflammation is most commonly caused by colonization of the gut by pathogens (bacteria or viruses). Learn more about this in the Importance a Balanced Gut Microbe Ratio in the Gut.

Strangulation (or Gut Torsion or Twisting) Colic: A twist occurring in the gut causes strangulation colic, which often cuts off blood supply and results in dying tissue. This type of colic is very serious and the most likely to be fatal.

Enterolith: Enteroliths are mineral accumulations of magnesium-ammonium-phosphate (struvite) around a foreign object (a piece of metal, pebble, bailing twine, hair, rubber) that form round, triangular, or flat stones inside the bowel usually over the course of multiple years. They form in the large colon of horses where they can remain for some time until they move and cause an obstruction in the large or small colon, resulting in colic.

Idiopathic or Spasmodic Colic: The majority of colic cases are idiopathic. This means the cause is unknown or unable to be determined. This is a wide-ranging term for horses presenting with colic where other abnormalities cannot be found, and, which generally have increased gut movement (and therefore gut noise if you listen over the belly). The colic signs are associated with increased gut spasm due to the increase in motility (a horse equivalent to gut cramps that we may experience after a very spicy curry for example). Rectal examination is within normal limits in these cases and, these horses often respond very favorably to drugs that decrease gut motility (see treatment of colic).

Treatment Options:

Your vet may carry out the following to try to diagnose the type of colic:

- Checking your donkey’s heart rate and temperature.

- Listening to your donkey’s abdomen with a stethoscope to check the gut sounds

- Checking your donkey’s teeth

- Taking a blood sample

- Performing a rectal examination

- Passing a stomach (nasogastric) tube to check for reflux (backed up food or fluid).

Your vet will decide on the best treatment based on your donkey’s diagnosis and are likely to give painkillers. - Depending on their findings, your vet may give your donkey fluids via a nasogastric tube or put them on a ‘drip’ (usually via the large vein in their neck). It may take multiple visits from your vet to treat your donkeys colic.

- Your donkey may need to be hospitalised if their case is severe. If your donkey is hospitalised, their companion must go too, as hospitalisation can be very stressful for donkeys. Some types of colic need surgery to resolve them, which will require prompt transport to a hospital. Surgery carries a high risk in most colic cases and involves considerable nursing care and cost. Check you are insured for the costs and talk to your vet about the chances of success.

- Euthanasia may be the kindest option if your donkey’s case is serious.

Prevention:

Colic is so dangerous because by the time your donkey lets you know it has colic, it may be too late to save it. The old adage, ‘prevention is better than cure’, definitely applies.

Observe your donkey daily, looking for any changes in behaviour. Know what typical dung looks like. Be aware of the average number of piles of droppings your donkeys pass each day and the consistency. Persistently very loose or very dry droppings could be indicative of colic, particularly if other symptoms appear. Check your donkey’s breathing pattern so you will be able to spot any change.

Colic Causes & Prevention:

- Feed – sudden changes to diet, poor quality feed, too much grass, feeding cereals:

- Make any dietary changes gradually over at least a week, ideally 2-4 weeks

- Feed good quality forage and donkey specific proprietary feeds

- Avoid moldy feed

- Always soak sugar beet to the manufacturer’s recommendations

- Feed little and often, especially if your donkey has additional feed

- Do not allow your donkey access to too much rich spring grass.

- Inadequate or dirty water supply:

- Check troughs daily. Self-filling drinkers can become blocked, or the water supply can fail

- Clean dirty water containers as donkeys will not drink dirty water

- Check water is not frozen or too cold. Many donkeys will not drink very cold water

- Offer several sources of water.

- Eating non-food items such as plastic bags, rope or bedding:

- Ensure your donkeys cannot access non-food items

- Change your donkey’s bedding to something less palatable, such as wood shavings

- Do not use cardboard or paper bedding.

- Eating poisonous plants:

- Know your poisonous plants and trees

- Remove poisonous plants or fence off the problem area

- Check pasture, boundary fences and hedgerows frequently

- Fence off trees when fruiting to prevent your donkey gorging.

- Sandy soil:

- Avoid grazing on sandy soil pasture if possible.

- Dental disease – failure to chew food adequately resulting in a blockage of the gut:

- Have your donkey’s teeth checked at least annually by a qualified equine dental technician or vet

- Dental disease is more common in older donkeys

- Suspect dental problems if donkeys are ‘quidding’ (dropping part chewed feed) or drooling saliva

- Parasites – worms causing obstruction or inflammation of the gut:

- Arrange regular faecal worm egg counts to check if your donkey needs treating for worms

- Speak to your vet for advice

- Clear droppings from your donkey’s paddock at least twice a week.

- Stomach ulcers:

- Keep stress to a minimum

- Trickle feed your donkey.

- Pain – any painful condition can lead to colic, including severe lameness:

- Ensure your donkey has adequate pain relief if they have a painful condition.

More Information:

https://vetmed.illinois.edu/pet-health-columns/colic-comes-many-forms/

https://extension.psu.edu/colic-what-are-the-signs-and-how-to-manage