Tag Archives: horses

Tornado Preparedness with Horses

You’re Always with Me

Tonight I lost my best friend, Chance. The one who whinnied the moment my car pulled up, would run away and wait for me to catch him only to turn around and run away again. He made me laugh, knew all my secrets and nuzzled me when I was sad. He taught me about unconditional love and having a positive attitude despite circumstances. He nodded when I asked if he loved me and gave kisses to get treats. He’s the 17.1 hand horse who would stand behind me and fall asleep as I did my school work and would get upset if any horse got near me but would never hurt a fly. He let children hug him and dogs run into his stall and let me dress him up with flowers. He loved rolling in the snow, laying in the sunshine, and would light up the moment he saw me. I’ll miss playing in the barn on cold nights and curling up reading in his stall when he wasn’t feeling well. I’m thankful that he waited for me to get there tonight to say goodbye so I could hold his head in my lap and talk to him while he passed. There will never be a sweeter horse with a more gentle and pure soul. Thank you, Bubba, for being with me through it all- high school, college, the break ups, the losses, the good and bad days. You gave one hell of a fight for 30+ years. Lucky and I will miss you- there will never be another you❤️ #myfavoriteredhead #chancewetake #20yearstogether #thebesthorseintheworld #myheart

It’s Raining…Lets Play!

Your Horse is Not a Therapist

Your Horse Is Not a Therapist

(But They Are Good Medicine)

This and other notes on horses and depression

When I teach horse riding to friends and family, I use like and as like trailer hitches: they pull my students into different concepts while they are in the saddle.

“Hold the reins like a baby bird.”

“Imagine the horse as a river, and your legs as the banks guiding the river along.”

“I want you to push down through your heels like you could break the stirrups.”

Unlike riding, the metaphors I use for depression never describe it with much accuracy. Depression is at once an absence of things and a too much of things, a void, a slowing down, a speeding up, it’s too much and too little.

Instead, my depressive episodes are blotted, memories. They are moments half-vacant. The first time I remember having symptoms, all I could pull up from the database of my memory was the hum of my parents’ air conditioner at eleven in the morning. It was gurgling. Droning thuds right outside the door where I slept. It was the summer of 2008, the gas prices rose, the economy crumbled, and the coda of my existence was staying in bed because there was no point in getting out of it.

It went away when I went back to school the following autumn. Or, at least, I thought it did. I can still hear the echoes of school friends, telling me that maybe there was more to my melancholy than just sadness and being a chronic overachiever.

I ignored them.

After college, I lived on a horse farm in rural Colorado. It had a million-dollar view of slotted canyons and farm fields stretching for miles. Most days I rolled out of bed by 7:00am, fed 20 horses, cleaned out their runs for the day, did chores, and then wrote website copy for a marketing agency in a little office that faced east.

I remember the raccoons squabbling over the dumpster at night, the echo of coyotes after a kill, and the thrill of a shooting star streaking the sky with luminous urgency. I loved riding just before sunset, watching the red dust cast clouds behind the horses hooves. I can also remember waves of nauseating numb and a strange sense of dread that never really lifted. Some days didn’t pass, they army-crawled.

The rhythm of farm life masked my symptoms. I have what doctors call “high functioning” clinical depression: it never mattered how crappy I felt or how existential I got or how much of a mess my relationships became, horses still needed to be fed, water troughs cleaned, and manure cleared away. Cowgirls don’t cry.

I DIDN’T UNDERSTAND THAT I WAS SICK.

Now almost five years since I first lived on that farm, I know that I can do most basic things when I am depressed. I can go to the grocery store, pay bills and answer the phone. I am one of the lucky ones.

What I can’t do is notice details. I can’t write, stay organized, or meet deadlines. I stop being able to pick up after myself or see anything as worthwhile. I eat too much or too little; sleep becomes a curse and a blessing. Before I knew I had depression, I would just blame my lack of self-discipline. I thought it was my dyslexia, a character flaw, or maybe I just wasn’t getting enough sleep. I told myself I needed to get up earlier, eat better, or drink more coffee. I didn’t understand that I was sick.

It is very unlikely I could have known I had depression. I had no idea what depression was.

My understanding of mental illness came from one high school production of David and Lisa and two 100 level psychology courses that still presented mental illness as uncommon. I thought anxiety was a normal state of being and depression was just bouncing, egg-shaped heads that smiled and talked about sexual side effects in Zoloft commercials.

Besides, I got to spend a lot of time with horses; my beliefs told me that if I had everything I wanted there was just no way I could be depressed. But that was exactly what was happening.

Depression or major depressive disorder as defined by the American Psychiatric Association is “a common and serious medical illness that negatively affects how you feel, the way you think and how you act.” Common symptoms include lack of energy, becoming withdrawn and numb to your environment, a sense of dread, despair, guilt, or worthlessness. It is also common for depressives to isolate themselves and stop doing the things they care about. It can impact sleeping and eating patterns and can show a drastic shift in behavior and personality. While these are the most common symptoms, each case varies from person to person, episode to episode.

For us farm folk of the world, this may seem flowery and self-involved. Me, a few years ago would have said, “Oh how sad for you, now get up and get stuff done.”

No matter my shame and judgment, the dollar signs in front of depression are staggering and very, very real. A 2015 study showed depression cost the United States $210 billion every year, this accounts for everything from lost wages, to treatment and other direct and indirect costs and losses. If it was a fake disease like I once believed it was, shouldn’t it be cheaper?

If the cost in dollars and cents weren’t enough to leave us blushing over the manure pile, the number of people with the disease should do the trick. The National Alliance on Mental Illness reports that more that 43.8 million Americans suffered from some form of mental illness in 2015. This is just under one in five Americans.

Depression, which is the most common mood disorder, is also recognized by the Center for Disease Control as “a serious medical illness and an important public health issue.” Thus while we would all love to say, that depression and other mental illness never enters into the barn, the facts are stacked against us.

There is a t-shirt in many horse catalogs that says “My horse is my therapist.” I once would have purchased it in a couple of different colors. Now, as the resident Captain Killjoy of the barn, I want to say, “Cool, maybe they’ll make ‘My horse is my Chemotherapy,’ or how about this potential best-seller ‘My horse is my fast-acting inhaler.’”

If you just found the second two offensive, then yes, the first one is too. The reason it is problematic is not because our time with horses isn’t therapeutic. But rather because it diminishes mental illness as a lesser, illegitimate disease.

I, too, fell for the ethos of the horse as a cure-all for mental illness. I once thought therapy and psychiatric medication was for bored, wealthy people and the occasional hypochondriac. I also thought it was only effective for those with really low functioning diagnoses and meth addicts.

I WAS A FARM GIRL, STRANGERS TOLD ME I SEEMED TOUGH. WHO WAS I IF I LOST THAT?

On the other hand, I was also terrified. My imagination told me that if I went to a therapist, I’d be institutionalized like I had seen in the movies or I’d be the one thing I had convinced myself I was not: weak.

I was a horse person; I was a farm girl, strangers told me I seemed tough. Who was I if I lost that?

I would never think I was weak if I went to the emergency room because I got chucked off a horse and landed badly. I also wouldn’t think I was weak if I went to a doctor because I caught pneumonia after breaking the ice out of water buckets. The same logic should have applied to seeking treatment for depression.

Yet, when I talked myself into making an appointment with the mental health department I spent the entire phone call to the doctor in a cold sweat. I also considered running out of the waiting room in a panic before my first consultation had even started. Old stigmas against mental illness are a hard thing to silence, even if that mental illness is slowly trying to kill you.

Treatment turned out to be nothing like I imagined. There was minimal mood lighting, pedantic banter or forced breathing exercises. Therapy and treatment turned out to be very much like taking riding lessons. I paid a therapist for the same reason I paid a riding instructor: to notice things. They used their training and expertise and made me better. Just like a riding instructor had shown me that I had a nasty habit of letting the horse fall in at the corner, a therapist showed me how my emotional patterns were making me sicker. After noting the problem, they then gave me strategies to improve.

IT IS STILL A PART OF MY LIFE, BUT IT NO LONGER CONTROLS MY LIFE.

I know that if I had treated my depression sooner, I would have enjoyed my days on the farm more, I would have ridden more, worked harder, and laughed more. I would have been a better advocate for the horses I rode. If I had started therapy sooner, I would have ridden better, too. I would have spent the time noting reality, instead of simply trying to stay afloat in a soup of depression induced self-deprecation.

I am still not free of depression but because I understand it, I am better at taking care of myself when it appears. It is still a part of my life, it probably always will be, but it no longer controls my life.

You may, at this point, think I have sworn off horses as medicine altogether. If I had struggled that hard with depression when I was around horses every day, you might be surprised to hear that I do believe that horses are a valid way to help treat depression and other mental illnesses.

“Help treat” is the key statement here. My feelings on equine therapy for mental illness simply hold more specific parameters than they once did. I believe that if equine therapy is a primary treatment then it should be done in the company of a trained professional. In fact, this kind of therapy on horseback or in the company of horses is done all over the world and has been used to treat everyone from teens with severe anxiety, to veterans with PTSD, to those incarcerated. While research on the effectiveness of equine-based therapy for mental illness is still in its early stages, early studies show promise.

Time with horses have proven to be one of my best forms of secondary treatment to supplement therapy and medication. One of the beautiful things about depression, notes psychology writer Andrew Solomon, is that it is a disease that impacts the way we feel. If someone has diabetes, lunges a horse, and feels better, they will still leave the round pen with diabetes. If someone goes into a round pen with depression and lunges a horse makes them feel better, then for that moment it is an effective treatment for depression.

Exercise is also often a key component in treating depression and, for many, being around horses is a good excuse for doing just that. It also can provide a low-stress way to cut down on isolation as our interactions with horses can have lower social stakes than those with other people.

I now understand that cowgirls do cry and we should. Our time with horses should be a safe time to struggle and change and talk and perhaps find some relief from what ails us. If it is not, then it’s important to find out the reason why and do what we can to address it.

Asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness, it is a sign of agency and self-awareness and these are two things that I, as a horse person, have learned to admire.

Even if I can’t use metaphors to describe depression, I can use one to describe what it is like when it lifts. When the depression first lifts, it feels like the first time I correctly rode a flying lead change. There is a moment of flight, of release, of understanding and clarity that is so delicious I wish I could bottle it and keep it on a windowsill. It’s as if the mysterious thing that I had been prevented from understanding is now understood.

When depression is gone, I can see the steam curl from a sweaty horse in the morning light with a renewed sense of wonder. I can laugh at horse galloping at play in a pasture.

When my depression lifts, it is as though I can pull myself out of the dingy trailer of my despair and a long trail ride awaits, and my horse is already saddled.

About the Author

Gretchen Lida is an essayist and equestrian. Her work has appeared in Brevity, Earth Island Journal, Washington Independent Review of Books, and many others. She has an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Columbia College Chicago and currently lives in Wisconsin. Follow her on Twitter at @GC_Lida.

Ice Packs & Horseshoes

Study Finds ‘Horse Bug’ in People is Caused by Actual Virus

Being obsessed with horses isn’t ‘a passion’ reveal researchers.

It’s a disease.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore have found that a heightened interest in horses and the compulsion to be around them at all times, is linked to the virus Ecus solidamentum.

“We’ve nicknamed the disease the ‘horse bug’,” says the study’s lead author, Dr. Ivan Toride. “But all joking aside, it seems to be a serious affliction that has real repercussions for sufferers.”

The study reports that people infected with Ecus solidamentum lose all rational thought processes when exposed to equines. Sufferers will ignore physical injuries, strained personal relationships and financial troubles just to spend more time with horses. Dr. Toride admits it’s a startling discovery to find a physical cause behind what was once thought to be only a mental affliction.

People generally become infected through mosquito bites, which is why those who already spend time in barns and outdoors with horses seem to be more susceptible. Interestingly, the researchers found infection rates are higher among middle-age women and that they are the most symptomatic when infected. Teenage girls also have a high susceptibility to the virus, but the disease seems to resolve itself in many by the time the girls reach their 20s.

“It’s a multi-faceted disease that will require much more investigation,” says Dr. Toride. “We still don’t understand the exact viral mechanism that affects the brain’s functioning, or why women in particular seem to be more susceptible.”

Anita Notherpony, who was infected with Ecus solidamentum last year, participated in Dr. Toride’s study. In the last 12 months, her behaviour around horses has become more erratic as the virus has spread through her body. “I lost my job because I couldn’t stay away from the barn. When I did go to work, all I did was read articles about horses or look at horses for sale,” she says.

“It started slowly, I thought it was just a new interest at first. But when I spent my entire pay check at the tack store, I began to suspect there was something deeper was at play.”

When Notherpony read about Dr. Toride’s research in an article in a horse magazine, a lightbulb went off. “I just said, ‘this is me.’”

Notherpony immediately contacted the research team for help. “Dr. Toride diagnosed me. At least I now have an explanation for what is happening. I know this disease is ruining my life, but it’s a compulsion I can’t control. I just hope they find a cure.”

Recently, Notherpony secretly sold her husband’s car for a third horse. At the time of this writing, it was unclear if her husband would be able to continue his employment without a way to get to work, leaving them both in a precarious financial situation.

Betraying the seriousness of her disease, a rapidly deteriorating Notherpony didn’t seem to be able to grasp the severity of the situation during an interview with Horse Network. “He’ll just have to find some other way to get to work. I need to buy another saddle next week,” she said.

It’s situations like these that are pushing Dr. Toride and his team to work overtime to find a cure for Ecus solidamentum. “It’s frightening to see how this disease can affect a mind. We can only hope we stumble across a cure soon,” he says.

Three Ways You May Be Inadvertently Putting Your Barn at Risk for Fire

More so than from other tragedies, I find myself physically as well as emotionally affected by these stories. As the horses usually have absolutely no chance of escaping, I think it is probably the horse owner’s worst nightmare.

Emotions aside, in my job as a professional electrician, I am mindful that many of these fires are caused by faulty electrical wiring or fixtures. Over the year,s I have borne witness to my share of potential and actual hazards. Designing a barn’s electrical system to today’s codes and standards is a topic for another day. For today, let’s address what we can do to make the existing horse barn safer.

I can’t cite statistics or studies, but my own experience shows the main safety issues that I am exposed to fall into three general categories:

- Using extension cords in place of permanent wiring

- Exposed lamps in lighting fixtures, and

- Overloading of branch circuits.

The first item I am addressing is extension cords.

I am often asked how extension cords can be UL-listed and sold if they are inherently unsafe. The answer is that cords are not unsafe when used as intended, but become so when used in place of permanent wiring.

The main concern is that most general purpose outlets in barns are powered by 15 or 20 ampere circuits, using 14 or 12 gauge building wiring, respectively. Most cords, however, for reasons of economy and flexibility, are rated for 8 or 10 amperes, and are constructed of 18 or 16 gauge wiring. That’s no problem if you are using the cord as intended—say, powering a clipper that only draws 1 to 4 amperes.

The problem comes when the cord is left in place, maybe tacked up on the rafters for the sake of “neatness.” You use it occasionally, but then winter comes and you plug a couple of bucket heaters into it. When the horses start drinking more water because it’s not ice cold, two buckets become four—or more.

If they draw 2.5 amperes each, you are now drawing 10 amperes on your 18 gauge extension cord that is only rated to carry 8 amperes. The circuit breaker won’t trip because it is protecting the building wiring, which is rated at 20 amperes. A GFCI outlet won’t trip either because the problem is an overload, not a ground fault.

Anyway, next winter, you decide to remove two of the buckets and add a trough outside the stall with a 1500 watt heater, which draws 12.5 amps at 120 volts. If you thought of it, you even replaced the old 18 gauge cord with a 16 gauge one that the package called “heavy duty.” Now the load is 17.5 amperes on a cord that is designed to handle 10 amperes.

In this case, it is possible to overload a “heavy duty” cord by using it at 175% of its rated capacity and never trip a circuit breaker. What has happened is, we’ve begun to think of the extension cord as permanent wiring, rather than as a temporary convenience to extend the appliance cord over to the outlet.

In doing so, we have created an unsafe condition.

Overloaded cords run hot. Heat is the product of too much current flowing over too small a wire. The material they are made of isn’t intended to stand up over time as permanent wiring must. It’s assumed that you will have the opportunity to inspect it as you unroll it before each use.

The second item on our list is exposed lamps (bulbs) in lighting fixtures.

Put simply, they don’t belong in a horse barn. A hot light bulb that gets covered in dust or cobwebs is a hazard. A bulb that explodes due to accumulating moisture, being struck by horse or human, or simply a manufacturing defect introduces the additional risk of a hot filament falling onto a flammable fuel source such as hay or dry shavings.

In the case of an unguarded fluorescent fixture, birds frequently build nests in or above these fixtures due to the heat generated by the ballast transformers within them. Ballasts do burn out, and a fuel source—such as that from birds’ nesting materials—will provide, with oxygen, all the necessary components for a fire that may quickly spread to dry wood framing.

The relatively easy fix is to use totally enclosed, gasketed and guarded light fixtures everywhere in the barn. They are known in the trade as vaporproof fixtures and are completely enclosed so that nothing can enter them, nothing can touch the hot lamp, and no hot parts or gases can escape in the event of failure.

The incandescent versions have a cast metal wiring box, a Pyrex globe covering the lamp, and a cast metal guard over the globe. In the case of the fluorescent fixture, the normal metal fixture pan is surrounded by a sealed fiberglass enclosure with a gasketed lexan cover over the lamps sealed with a gasket and secured in place with multiple pressure clamps.

The last item, overloaded branch circuits, is not typically a problem if the wiring was professionally installed and not subsequently tampered with. If too much load is placed on a circuit that has been properly protected, the result will be only the inconvenience of a tripped circuit breaker.

The problem comes when some “resourceful” individual does a quick fix by installing a larger circuit breaker. The immediate problem, tripping of a circuit breaker, is solved, but the much more serious problem of wiring that is no longer protected at the level for which it was designed, is created.

Any time a wire is allowed to carry more current than it was designed to, there is nothing to stop it from heating up to a level above which is considered acceptable.

Unsafe conditions tend to creep up on us—we don’t set out to create hazardous conditions for our horses.

Some may think it silly that the electrical requirements in horse barns (which are covered by their own separate part of the National Electric Code) are in many ways more stringent than those in our homes.

I believe that it makes perfect sense. The environmental conditions in a horse barn are much more severe than the normal wiring methods found in the home can handle. Most importantly, a human can usually sense and react to the warning signals of a smoke alarm, the smell of smoke, or of burning building materials and take appropriate action to protect or evacuate the occupants. Our horses, however, depend on us for that, so we need to use extra-safe practices to keep them secure.

As I always state in closing my electrical safety discussions, I know that we all love our animals. Sometimes in the interest of expedience, we can inadvertently cause conditions that we never intended. Electrical safety is just another aspect of stable management. I often use the words of George Morris to summarize:

“Love means giving something our attention, which means taking care of that which we love. We call this stable management.”

About the Author

Thomas Gumbrecht began riding at age 45 and eventually was a competitor in lower level eventing and jumpers. Now a small farm owner, he spends his time working with his APHA eventer DannyBoy, his OTTB mare Lola, training her for a second career, and teaching his grandson about the joy of horses. He enjoys writing to share some of life’s breakthroughs toward which his horses have guided him.

Keeping Your Horse Safe on the 4th of July

When I think of the Fourth of July, I think of a fun time with my family and friends. Typically, I am not thinking of the potentially hazardous effects the fireworks may have on my animals…. Why would you? However, the truth is, the boom of the fireworks and the bright and sudden flashes can not only cause our horses severe anxiety but may also lead to injury.

Have you ever been in the dark and someone shines a flashlight in your eyes? What happens? You see spots. You are momentarily unable to see. Your balance gets thrown off and you can’t tell what is right in front of you. Well, imagine a horse. He is in a dark paddock and suddenly flashes of light momentarily blind him and add in the boom…recipe for disaster. Not only can he barely see but he spooks from the noise. The results could be anxiety to tripping and breaking a leg. That being said, I have included some useful information below for ways to safeguard your horse this July 4th.

Fireworks and Horses: Preparing for the Big Boom | TheHorse.com

Immune Booster Leads to Infection?

For the past 6 weeks, my horse has been receiving Ozonetherapy to aid in his chronic back leg related issues- dermatitis (“scratches”), previous DDFT tendon laceration, a history of Lymphingitis, and the residual scar tissue from his DDFT injury. Due to his age (27), he lacks proper circulation in his hind end which does not help him fight his pastern dermatitis.

According to the American Academy of Ozonetherapy, Ozonetherapy is described as;

“Ozonotherapy is the use of medical grade ozone, a highly reactive form of pure oxygen, to create a curative response in the body. The body has the potential to renew and regenerate itself. When it becomes sick it is because this potential has been blocked. The reactive properties of ozone stimulate the body to remove many of these impediments thus allowing the body to do what it does best – heal itself.”

“Ozonotherapy has been and continues to be used in European clinics and hospitals for over fifty years. It was even used here in the United States in a limited capacity in the early part of the 20th century. There are professional medical ozonotherapy societies in over ten countries worldwide. Recently, the International Scientific Committee on Ozonotherapy (ISCO3) was formed to help establish standardized scientific principles for ozonotherapy. The president of the AAO, Frank Shallenberger, MD is a founding member of the ISCO3.”

“Ozonotherapy was introduced into the United States in the early 80’s, and has been increasingly used in recent decades. It has been found useful in various diseases;

- It activates the immune system in infectious diseases.

- It improves the cellular utilization of oxygen that reduces ischemia in cardiovascular diseases, and in many of the infirmities of aging.

- It causes the release of growth factors that stimulate damaged joints and degenerative discs to regenerate.

- It can dramatically reduce or even eliminate many cases of chronic pain through its action on pain receptors.

- Published papers have demonstrated its healing effects on interstitial cystitis, chronic hepatitis, herpes infections, dental infections, diabetes, and macular degeneration.”

After doing research and speaking to one of my good friends, we determined that Chance’s flare up of Lymphingitis, after almost 3 years of not a single issue, could possibly be caused by his immune system’s response to Ozonetherapy. Let me explain.

Chance suffers from persistent Pastern dermatitis (“scratches”) since I purchased him in 2000. I have tried everything- antibiotics, every cream and ointment and spray for scratches, diaper rash ointment, iodine and vaseline mix, Swat, laser treatments, scrubs and shampoos, shaving the area, wrapping the area, light therapy…you name it, I have tried it. So, when we began Ozonetherapy to help break down the left over scar tissue from his old DDFT injury, I noticed that his scratches were drying up and falling off. We continued administering the Ozonetherapy once a week for about 6 weeks. The improvement was dramatic!

However, one day Chance woke up with severe swelling in his left hind leg and obviously, he had difficulty walking. He received Prevacox and was stall bound for 24 hours. The vet was called and she arranged to come out the following day. The next morning, Chance’s left leg was still huge and he was having trouble putting weight on it. I did the typical leg treatments- icing, wrapping. The swelling remained. I tried to get him out of his stall to cold hose his leg and give him a bath but he would not budge. He was sweaty and breathing heavily and intermittently shivering. So, I gave him an alcohol and water sponge bath and continued to ice his back legs. I sat with him for 4 hours waiting for the vet to arrive. He had a fever and wasn’t interested in eating and his gut sounds were not as audible. He was drinking, going to the bathroom, and engaging with me. I debated giving him Banamine but did not want it to mask anything when the vet did arrive.

The vet arrived, gave him a shot of Banamine and an antihistamine and confirmed that Chance had a fever of 102 degrees and had Lymphingitis. There was no visible abrasion, puncture, or lump… I asked the vet to do x-rays to ensure that he did not have a break in his leg. The x-rays confirmed that there was no break. The vet suggested a regiment of antibiotics, steroids (I really am against using steroids due to the short-term and long-term side effects but in this case, I would try anything to make sure he was comfortable) , prevacox, and a antacid to protect Chance from stomach related issues from the medications. It was also advised to continue to cold hose or ice and keep his legs wrapped and Chance stall bound.

The following day, Chance’s legs were still swollen but his fever had broken. The vet called to say that the CBC had come back and that his WBC was about 14,00o. She suggested that we stop the steroids and do the antibiotic 2x a day and add in Banamine. I asked her if she could order Baytril (a strong antibiotic that Chance has responded well to in the past) just in case. And that is what we did.

Being as Chance had such a strong reaction to whatever it was, I did some thinking, discussing, and researching…first and foremost, why did Chance have such an extreme flare up of Lymphingitis when he was the healthiest he has ever been? And especially since he had not had a flare up in 3+ years…plus, his scratches were getting better not worse. The Ozonetherapy boosted his immune system and should provide him with a stronger defense against bacteria, virus’, etc. So why exactly was he having a flare up? And that is when it hit me!

In the past when Chance began his regiment of Transfer Factor (an all natural immune booster), he broke out in hives. The vet had come out and she felt it was due to the Transfer Factor causing his immune system to become “too strong” and so it began fighting without there being anything to fight, thus the hives. My theory- Chance started the Ozonetherapy and his body began to fight off the scratches by boosting his immune system. As the treatments continued, his immune system began to attack the scratches tenfold. This resulted in his Lymphatic system to respond, his WBC to increase, and his body temperature to spike. Makes sense…but what can I do to ensure this is not going to happen again?

My friend suggested attacking the antibiotic resistant bacteria by out smarting them…okay, that seems simple enough…we researched the optimal enviroments for the 3 types of bacteria present where Chance’s scratches are (shown in the results of a past skin scape test). The bacteria – E. Coli, pseudomonas aeruginosa and providencia Rettgeri. The literature stated that PA was commonly found in individuals with diabetes…diabetes…SUGAR! How much sugar was in Chance’s feed? I looked and Nutrina Safe Choice Senior feed is low in sugar…so that is not it. What else can we find out? The optimal temperature for all three bacteria is around 37 degrees celsius (or 98.6 degrees fahrenheit), with a pH of 7.0, and a wet environment. Okay, so, a pH of 7.0 is a neutral. Which means if the external enviroment (the hind legs)pH is thrown off, either to an acidic or alkaline pH, the bacteria will not have the optimal enviroment to continue growing and multiplying. How can I change the pH?

Vinegar! An antimicrobial and a 5% acetic acid! And…vinegar is shown to help kill mycobacteria such as drug-resistant tuberculosis and an effective way to clean produce; it is considered the fastest, safest, and more effective than the use of antibacterial soap. Legend even says that in France during the Black Plague, four thieves were able to rob the homes of those sick with the plague and not become infected. They were said to have purchased a potion made of garlic soaked in vinegar which protected them. Variants of the recipe, now called “Four Thieves Vinegar” has continued to be passed down and used for hundreds of years (Hunter, R., 1894).

I went to the store, purchased distilled vinegar and a spray bottle and headed to the farm. I cleaned his scratches and sprayed the infected areas with vinegar. I am excited to see whether our hypothesis is correct or not…I will keep you posted!

References & Information

Effect of pH on Drug Resistent Bacteriaijs-43-1-174

What does my horse’s CBC mean?

Nutrena SC Senior feed ingredience

The American Academy of Ozonetherapy

Hunter, Robert (1894). The Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Toronto: T.J. Ford. ISBN 0-665-85186-3.

Summer Days

EPM Tilter. What Do The Numbers Mean?

During my horse’s recent Lymphingitis flare-up, the vet advised that we run labs to test for Lyme and EPM due to his presenting symptoms (hind weakness, twisting his back leg at the walk/walking sideways I refer to it as- “Chance’s swagger”). As I noted previously, Chance’s Lyme test revealed that he was at the beginning stages of an acute infection…yay for the labs at Cornell University for their amazing ability to give you more than a positive or negative!

A little history before getting to the EPM Tilter results.

About 2ish years ago, Chance was diagnosed with EPM (and one of the reasons opossums and I are not friends since they host the disease as do a few other culprits). Chance immediately began EPM treatment- he received Protazil in his feed for one month. After hours of research I chose Protazil, although extremely expensive (if you order from http://www.drfosterandsmith.com they sometimes have promotions where you receive store credit for every $100.00 you spend…they did when I ordered and I got a “free” dog bed that my dogs adore), due to the decreased likelihood of Chance experiencing a “Treatment Crisis” (worsening of symptoms) and the ease of administration (other brands require the drug being administered 1 hour before eating or an hour after and so on). Typically, EPM treatment is done for 30 days and, depending on the residual symptoms, some may require subsequent treatments. While Chance’s symptoms improved, I wanted to ensure that we annihilated the disease and did another round of treatment but this time with Marquis. At the end of two months, Chance’s ataxia was gone!

Fast forward to September 2016…Chance, just having a Lymphingitis flare-up, has been tested for Lyme and EPM. Lyme came back positive. And….so did the EPM test..well, kind of. Wonderful. (See why I loathe opossums?)

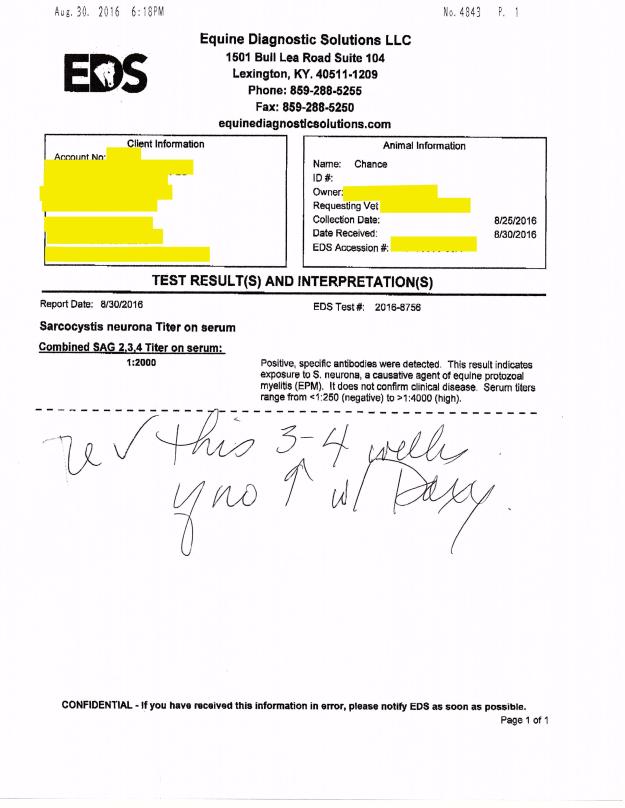

Chance’s EPM test #2 on 8/30/16 (the 1st one was 2ish years ago) showed the following:

“Combined SAG 2,3,4 Tilter on serum= 1:2000”

So, what does this mean?

The test revealed that Chance had “positive, specific antibodies” detected in the blood work. This means that he had EXPOSURE to S. Neurona, a causative agent of EPM. Serum tilters range from <1:250 (negative) to >1:4000 (high positive). S. Neurona (SarcoFluor) is one of two protozoa found in EPM infected horses, the other protazoa is N. Hughesil (NeoFluor). S. Neurona is most frequently seen, whereas N. Hughesil is not as common.

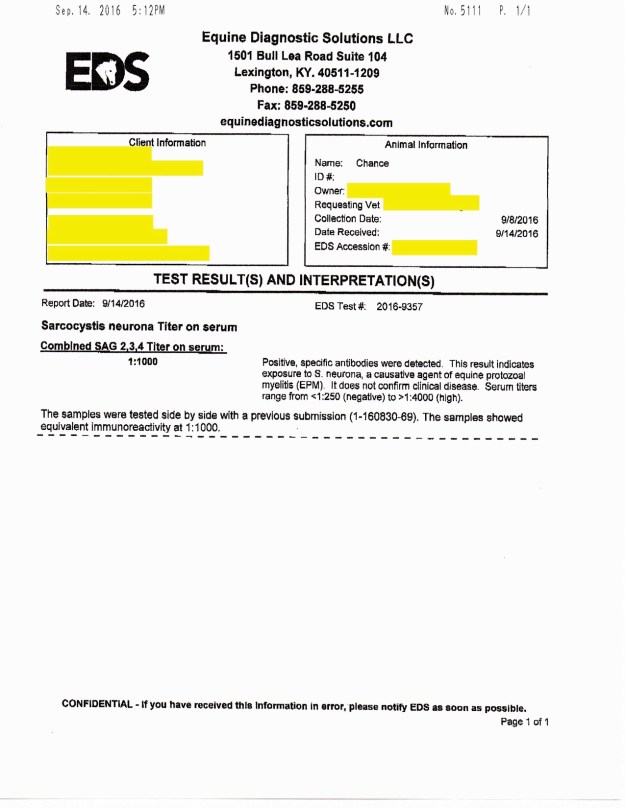

The vet ran another EPM test to confirm the findings in the 8/30/16 test. The results showed that Chance had “Combined SAG 2,3,4 Tilter on serum= 1:1000. Again, Chance showed EPM protozoa in the positive-ish range.

I initially had not seen the results but was told by the vet that he was EPM negative. So when I asked for the test results to be emailed to me and saw the numbers I sort of freaked out…I emailed the vet to ask for clarification. She explained,

“The EPM test shows that he was exposed to the organism in the first test we did which is why we did a follow-up test. Since his exposure level dropped from 1:2000 to 1:1000 this shows that he does not have the disease. There is no good one time test for EPM once they are exposed which is why we had to do the repeat to compare the two.”

While this explanation offered me comfort, I was confused…why does he have any protozoa in his blood if he doesn’t have EPM?

I spoke to another vet and she explained it in a bit more detail…I am hoping I am summarizing what she said correctly..

When a horse tests positive for EPM they either have an active disease or they may not. However, when the test does from 1:2000 down to 1:1000 this typically means that the horse’s immune system is working correctly to fight the disease off- active or not. EPM testing typically provides you with a % of the chance your horse has an active EPM infection, or at least if you send it to Cornell University. For instance, lets say a horse gets the results back and it shows that they are “positive” or have been exposed to S. Neurona (one of the two EPM protozoa)…their results are 1:647. This means that, after doing a bunch of adding and multiplying that this vet kindly did for me, the horse has a 60-70% chance of having ACTIVE EPM. Meaning, he most likely would be symptomatic (ie: behavioral changes, ataxia, weight loss, difficulty eating, changes in soundness, and a bunch of other neurological symptoms).

My hunch is that Chance’s immune system was boosted because I started him on Transfer Factor (amazing stuff… more information can be found in some of my older posts) again as soon as his results came back positive for Lyme.

Here are the 3 EPM tilters that were run on Chance (oldest to most recent) along with his Lyme test results:

I have a limp!

Resources on how to diagnose, treat, prevent, and handle lameness in horses

Your Horse Has a Swollen Leg – Why and What To Do | EquiMed – Horse Health Matters

Fetlock Lameness – It’s importance… | The Horse Magazine – Australia’s Leading Equestrian Magazine

Causes of Equine Lameness | EquiMed – Horse Health Matters

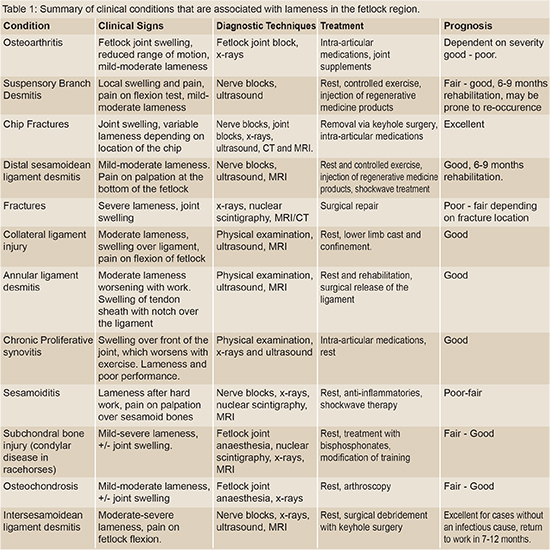

Common Causes of Lameness in the Fetlock

Flower Horses