BEST Guide to all Things Colitis, Diarrhea, and Intestinal Health

By Dr Sarah-Jane Wilson, Livestock Biosecurity Network Northern Regional Manager

Death, unfortunately, is one of the most inescapable elements of life and one that, when it occurs within the livestock production chain, raises a litany of biosecurity issues.

Animal carcasses can pose a serious risk to both human and animal health, can jeopardise biosecurity and impose a range of environmental impacts if not properly disposed of. These risks can include polluting water courses, spreading disease and interfering with community amenity.

The old practice of simply leaving a carcass anywhere in the paddock to rot simply does not stack up in a modern livestock industry where the implications of incorrect carcass management are better understood.

In fact, depending on where you live, there may be local, state or national regulatory requirements that relate to your on-farm waste management procedures and I encourage you to make yourself familiar with these obligations.

We strongly recommend carcass disposal is integrated into your on-farm biosecurity plan and that you consider the methods available to dispose of animal carcasses or animal waste products including hide, gut or bones after home slaughter or wool that is not suitable for baling. Another important consideration is the equipment you may need to assist in this disposal.

If you live on a small farm, your best alternative may be to engage a specialist disposal service as opposed to burial or on-site burning. Again, there may be some regulatory requirements for producers in higher density areas and I encourage you to seek the advice of your local council or departmental staff to ensure you adhere to any applicable guidelines. Generally speaking burial is often the most practical and preferred method of disposal on a small farm if you do not have access to a disposal service.

For all producers, your geographic location and common endemic diseases should be taken into consideration. For example, if you live in a botulism affected area, burning is the recommended and preferred method. Botulism spores can live in the soil for many years, so simply burying the carcass will not suffice.

If you have multiple sudden deaths in your herd or flock, and/or do not know the cause of death, then it is best practice to investigate. Your local veterinarian or animal health/biosecurity officer may be able to provide further information. If you suspect an emergency or unusual disease, you should report this as soon as possible to your local animal health authority.

For more information, the NSW Environmental Protection Agency and the Tasmanian Environmental Protection Agency provide some good advice, as do most of the other applicable state departments, on how to effectively and responsibly dispose of the livestock carcasses on your property.

Top tips

Choosing a site (Source: NSW EPA)

If the carcasses must be disposed of on-site, it is preferable to have:

Other pit considerations (Source: Tas EPA)

If you need to burn (Source: NSW EPA)

Planning ahead for what to do with a carcass or, multiple carcasses in the event of a natural disaster, can substantially reduce the stress of the moment. It can also make a dramatic contribution to the biosecurity soundness of your property and our greater livestock industries.

Here at LBN we’ve designed a small template to assist producers in thinking through the options that best work for them. This can be found at: http://www.lbn.org.au/farm-biosecurity-tools/on-farm-biosecurity-planning-tools/.

Ends

Spotting Lameness: The Game Plan

— Read on horsenetwork.com/2018/10/spotting-lameness-game-plan/

|

|

|

When I teach horse riding to friends and family, I use like and as like trailer hitches: they pull my students into different concepts while they are in the saddle.

“Hold the reins like a baby bird.”

“Imagine the horse as a river, and your legs as the banks guiding the river along.”

“I want you to push down through your heels like you could break the stirrups.”

Unlike riding, the metaphors I use for depression never describe it with much accuracy. Depression is at once an absence of things and a too much of things, a void, a slowing down, a speeding up, it’s too much and too little.

Instead, my depressive episodes are blotted, memories. They are moments half-vacant. The first time I remember having symptoms, all I could pull up from the database of my memory was the hum of my parents’ air conditioner at eleven in the morning. It was gurgling. Droning thuds right outside the door where I slept. It was the summer of 2008, the gas prices rose, the economy crumbled, and the coda of my existence was staying in bed because there was no point in getting out of it.

It went away when I went back to school the following autumn. Or, at least, I thought it did. I can still hear the echoes of school friends, telling me that maybe there was more to my melancholy than just sadness and being a chronic overachiever.

I ignored them.

After college, I lived on a horse farm in rural Colorado. It had a million-dollar view of slotted canyons and farm fields stretching for miles. Most days I rolled out of bed by 7:00am, fed 20 horses, cleaned out their runs for the day, did chores, and then wrote website copy for a marketing agency in a little office that faced east.

I remember the raccoons squabbling over the dumpster at night, the echo of coyotes after a kill, and the thrill of a shooting star streaking the sky with luminous urgency. I loved riding just before sunset, watching the red dust cast clouds behind the horses hooves. I can also remember waves of nauseating numb and a strange sense of dread that never really lifted. Some days didn’t pass, they army-crawled.

The rhythm of farm life masked my symptoms. I have what doctors call “high functioning” clinical depression: it never mattered how crappy I felt or how existential I got or how much of a mess my relationships became, horses still needed to be fed, water troughs cleaned, and manure cleared away. Cowgirls don’t cry.

I DIDN’T UNDERSTAND THAT I WAS SICK.

Now almost five years since I first lived on that farm, I know that I can do most basic things when I am depressed. I can go to the grocery store, pay bills and answer the phone. I am one of the lucky ones.

What I can’t do is notice details. I can’t write, stay organized, or meet deadlines. I stop being able to pick up after myself or see anything as worthwhile. I eat too much or too little; sleep becomes a curse and a blessing. Before I knew I had depression, I would just blame my lack of self-discipline. I thought it was my dyslexia, a character flaw, or maybe I just wasn’t getting enough sleep. I told myself I needed to get up earlier, eat better, or drink more coffee. I didn’t understand that I was sick.

It is very unlikely I could have known I had depression. I had no idea what depression was.

My understanding of mental illness came from one high school production of David and Lisa and two 100 level psychology courses that still presented mental illness as uncommon. I thought anxiety was a normal state of being and depression was just bouncing, egg-shaped heads that smiled and talked about sexual side effects in Zoloft commercials.

Besides, I got to spend a lot of time with horses; my beliefs told me that if I had everything I wanted there was just no way I could be depressed. But that was exactly what was happening.

Depression or major depressive disorder as defined by the American Psychiatric Association is “a common and serious medical illness that negatively affects how you feel, the way you think and how you act.” Common symptoms include lack of energy, becoming withdrawn and numb to your environment, a sense of dread, despair, guilt, or worthlessness. It is also common for depressives to isolate themselves and stop doing the things they care about. It can impact sleeping and eating patterns and can show a drastic shift in behavior and personality. While these are the most common symptoms, each case varies from person to person, episode to episode.

For us farm folk of the world, this may seem flowery and self-involved. Me, a few years ago would have said, “Oh how sad for you, now get up and get stuff done.”

No matter my shame and judgment, the dollar signs in front of depression are staggering and very, very real. A 2015 study showed depression cost the United States $210 billion every year, this accounts for everything from lost wages, to treatment and other direct and indirect costs and losses. If it was a fake disease like I once believed it was, shouldn’t it be cheaper?

If the cost in dollars and cents weren’t enough to leave us blushing over the manure pile, the number of people with the disease should do the trick. The National Alliance on Mental Illness reports that more that 43.8 million Americans suffered from some form of mental illness in 2015. This is just under one in five Americans.

Depression, which is the most common mood disorder, is also recognized by the Center for Disease Control as “a serious medical illness and an important public health issue.” Thus while we would all love to say, that depression and other mental illness never enters into the barn, the facts are stacked against us.

There is a t-shirt in many horse catalogs that says “My horse is my therapist.” I once would have purchased it in a couple of different colors. Now, as the resident Captain Killjoy of the barn, I want to say, “Cool, maybe they’ll make ‘My horse is my Chemotherapy,’ or how about this potential best-seller ‘My horse is my fast-acting inhaler.’”

If you just found the second two offensive, then yes, the first one is too. The reason it is problematic is not because our time with horses isn’t therapeutic. But rather because it diminishes mental illness as a lesser, illegitimate disease.

I, too, fell for the ethos of the horse as a cure-all for mental illness. I once thought therapy and psychiatric medication was for bored, wealthy people and the occasional hypochondriac. I also thought it was only effective for those with really low functioning diagnoses and meth addicts.

I WAS A FARM GIRL, STRANGERS TOLD ME I SEEMED TOUGH. WHO WAS I IF I LOST THAT?

On the other hand, I was also terrified. My imagination told me that if I went to a therapist, I’d be institutionalized like I had seen in the movies or I’d be the one thing I had convinced myself I was not: weak.

I was a horse person; I was a farm girl, strangers told me I seemed tough. Who was I if I lost that?

I would never think I was weak if I went to the emergency room because I got chucked off a horse and landed badly. I also wouldn’t think I was weak if I went to a doctor because I caught pneumonia after breaking the ice out of water buckets. The same logic should have applied to seeking treatment for depression.

Yet, when I talked myself into making an appointment with the mental health department I spent the entire phone call to the doctor in a cold sweat. I also considered running out of the waiting room in a panic before my first consultation had even started. Old stigmas against mental illness are a hard thing to silence, even if that mental illness is slowly trying to kill you.

Treatment turned out to be nothing like I imagined. There was minimal mood lighting, pedantic banter or forced breathing exercises. Therapy and treatment turned out to be very much like taking riding lessons. I paid a therapist for the same reason I paid a riding instructor: to notice things. They used their training and expertise and made me better. Just like a riding instructor had shown me that I had a nasty habit of letting the horse fall in at the corner, a therapist showed me how my emotional patterns were making me sicker. After noting the problem, they then gave me strategies to improve.

IT IS STILL A PART OF MY LIFE, BUT IT NO LONGER CONTROLS MY LIFE.

I know that if I had treated my depression sooner, I would have enjoyed my days on the farm more, I would have ridden more, worked harder, and laughed more. I would have been a better advocate for the horses I rode. If I had started therapy sooner, I would have ridden better, too. I would have spent the time noting reality, instead of simply trying to stay afloat in a soup of depression induced self-deprecation.

I am still not free of depression but because I understand it, I am better at taking care of myself when it appears. It is still a part of my life, it probably always will be, but it no longer controls my life.

You may, at this point, think I have sworn off horses as medicine altogether. If I had struggled that hard with depression when I was around horses every day, you might be surprised to hear that I do believe that horses are a valid way to help treat depression and other mental illnesses.

“Help treat” is the key statement here. My feelings on equine therapy for mental illness simply hold more specific parameters than they once did. I believe that if equine therapy is a primary treatment then it should be done in the company of a trained professional. In fact, this kind of therapy on horseback or in the company of horses is done all over the world and has been used to treat everyone from teens with severe anxiety, to veterans with PTSD, to those incarcerated. While research on the effectiveness of equine-based therapy for mental illness is still in its early stages, early studies show promise.

Time with horses have proven to be one of my best forms of secondary treatment to supplement therapy and medication. One of the beautiful things about depression, notes psychology writer Andrew Solomon, is that it is a disease that impacts the way we feel. If someone has diabetes, lunges a horse, and feels better, they will still leave the round pen with diabetes. If someone goes into a round pen with depression and lunges a horse makes them feel better, then for that moment it is an effective treatment for depression.

Exercise is also often a key component in treating depression and, for many, being around horses is a good excuse for doing just that. It also can provide a low-stress way to cut down on isolation as our interactions with horses can have lower social stakes than those with other people.

I now understand that cowgirls do cry and we should. Our time with horses should be a safe time to struggle and change and talk and perhaps find some relief from what ails us. If it is not, then it’s important to find out the reason why and do what we can to address it.

Asking for help isn’t a sign of weakness, it is a sign of agency and self-awareness and these are two things that I, as a horse person, have learned to admire.

Even if I can’t use metaphors to describe depression, I can use one to describe what it is like when it lifts. When the depression first lifts, it feels like the first time I correctly rode a flying lead change. There is a moment of flight, of release, of understanding and clarity that is so delicious I wish I could bottle it and keep it on a windowsill. It’s as if the mysterious thing that I had been prevented from understanding is now understood.

When depression is gone, I can see the steam curl from a sweaty horse in the morning light with a renewed sense of wonder. I can laugh at horse galloping at play in a pasture.

When my depression lifts, it is as though I can pull myself out of the dingy trailer of my despair and a long trail ride awaits, and my horse is already saddled.

About the Author

Gretchen Lida is an essayist and equestrian. Her work has appeared in Brevity, Earth Island Journal, Washington Independent Review of Books, and many others. She has an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Columbia College Chicago and currently lives in Wisconsin. Follow her on Twitter at @GC_Lida.

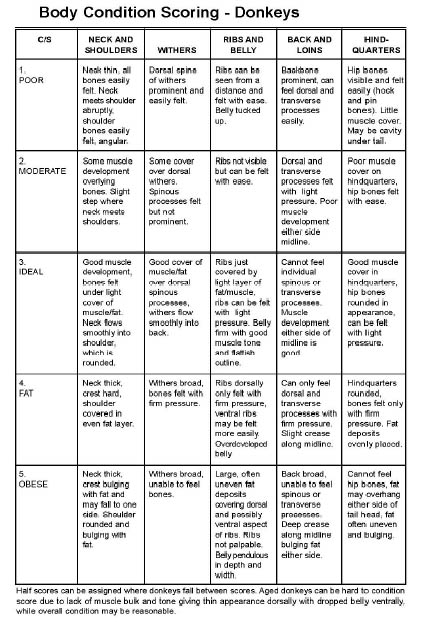

I have been desperately trying to get my miniature donkey, Lucky, to drop some lbs. The thing with Lucky- he literally gained weight overnight. One day he was a skinny mini and the next he had a potbelly. I was really concerned that the weight suddenly appeared and had the vet run a heptic panel to ensure he wasn’t experiencing some sort of liver dysfunction. Sort of like how humans can develop Ascites when they have liver related disease. Anyways, his blood work came back and all was okay….he was just fat!

Unlike horses, donkeys develop “fat deposits” around their neck, abdomen, and butt and even once the weight has been lost the deposits stay for life!

The Dangers of Obesity in Donkeys

According to the Scarsdale Vets;

“Obesity increases the risk of developing hyperlipaemia and laminitis, both of which can be fatal. Prevention of obesity is better than cure, because rapid loss of condition in overweight donkeys can trigger hyperlipaemia.

Hyperlipaemia is a condition in which triglycerides (fats) are released into the circulation which can result in organ failure and death unless treated rapidly. The early signs of dullness and reduced appetite can be difficult to detect. Hyperlipaemia can be triggered by anything that causes a reduction in food intake e.g. stress, transport, dental disease.

Laminitis is a condition in which there is inflammation in the laminae of the foot that connect the pedal bone to the hoof wall. This can progress to rotation or sinking of the pedal bone within the foot. The cause is not fully understood and many factors are involved but obese animals are more prone to develop the disease.”

Equine Metabolic Syndrome: “Overweight donkeys often develop a fat, crest neck and fat pads around their tail base. When this occurs the donkey can develop a metabolic disease known as ‘Equine Metabolic Syndrome’. This causes insulin resistance and increased levels of blood glucose (blood sugar) in the blood stream. In equids this can lead to recurrent episodes of laminitis or founder. This disease involves inflammation of the white lining or laminar junctions of the feet, extreme foot pain and difficulty walking. In severe cases this can also cause changes in the bone of the foot and hoof wall” (Yarra Ranges Animal Clinic)

How To Help Your Donkey Lose Weight Safely

Donkey Related Resources and Information

DonkeyBCS3posterDonkey Body Scoring by Dr_ Judy Marteniuk

Over the past 30 years the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation has funneled nearly $20 million into studies aimed at improving horse health. This year the effort continues with funding for a dozen new projects in fields ranging from laminitis to lameness diagnosis. A sampling:

Detecting lameness at the gallop: Kevin Keegan, DVM, of the University of Missouri, is developing an objective method (using a calibrated instrument) for detecting obscure, subtle lameness in horses at the gallop. The goal is a low-cost method that can be used in the field to increase understanding of lameness in racehorses.

Deworming and vaccines: While it’s not unusual to deworm and vaccinate horses on the same day, recent findings have raised concerns about possible interactions. Martin Nielsen, DVM, of the University of Kentucky and Gluck Equine Research Center, is investigating whether deworming causes an inflammatory reaction that affects vaccination.

Imaging injured tendons: Horses recovering from tendon injuries are often put back to work too soon and suffer re-injury. Sabrina Brounts, DVM, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is exploring a new method developed at the university to monitor healing in the superficial digital flexor tendon. The technique, called acoustoelastography, relates ultrasound wave patterns to tissue stiffness: Healthy tendon tissue is stiffer than damaged tissue.

Detecting laminitis early: Hannah Galantino-Homer, VMD, of the University of Pennsylvania, is investigating possible serum biomarkers (molecular changes in blood) that appear in the earliest stages of laminitis. The goal is to develop tests for these disease markers so that treatment can start when laminitis is just developing, before it’s fullblown and damages the foot.

Other new studies include evaluations of a rapid test for salmonella; investigation of how neurologic and non-neurologic equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) spreads cell-to-cell in the body; an effort to map the distribution of stem cells after direct injection into veins; and more.

This article originally appeared in the June 2013 issue of Practical Horseman.

Researchers are testing an endoscopic camera, contained in a small capsule and placed directly into the horse’s stomach, to gather imagery of the equine intestinal tract. The capsule sends images to an external recorder, held in place by a harness.

Courtesy, Western College of Veterinary Medicine

Traditionally, veterinarians’ and researchers’ view of the equine intestinal tract has been limited. Endoscopy (inserting through the horse’s mouth a small camera attached to a flexible cable to view his insides) allows them to see only as far as the stomach. While ultrasound can sometimes provide a bigger picture, the technology can’t see through gas—and the horse’s hindgut (colon) is a highly gassy environment.

These limitations make it hard to diagnose certain internal issues and also present research challenges. But the view is now expanding, thanks to a “camera pill” being tested by a team at the University of Saskatchewan, led by Julia Montgomery, DVM, PhD, DACVIM. Dr. Montgomery worked with a multi-disciplinary group, including equine surgeon Joe Bracamonte, DVM, DVSc, DACVS, DECVS, electrical and computer engineer Khan Wahid, PhD, PEng, SMIEEE, a specialist in health informatics and imaging; veterinary undergraduate student Louisa Belgrave and engineering graduate student Shahed Khan Mohammed.

In human medicine, so-called camera pills are an accepted technology for gathering imagery of the intestinal tract. The device is basically an endoscopic camera inside a small capsule (about the size and shape of a vitamin pill). The capsule, which is clear on one end, also contains a light source and an antenna to send images to an external recording device.

The team thought: Why not try it for veterinary medicine?

They conducted a one-horse trial using off-the-shelf capsule endoscopy technology. They applied sensors to shaved patches on the horse’s abdomen, and used a harness to hold the recorder. They employed a stomach tube to send the capsule directly to the horse’s stomach, where it began a roughly eight-hour journey through the small intestine.

The results are promising. The camera was able to capture nearly continuous footage of the intestinal tract with just a few gaps where the sensors apparently lost contact with the camera. For veterinarians, this could become a powerful diagnostic aid for troubles such as inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. It could provide insight on how well internal surgical sites are healing. It may also help researchers understand normal small-intestine function and let them see the effect of drugs on the equine bowel.

The team did identify some challenges in using a technology designed for humans. They realized that a revamp of the sensor array could help accommodate the horse’s larger size and help pinpoint the exact location of the camera at any given time. That larger size also could allow for a larger capsule, which in turn could carry more equipment—such as a double camera to ensure forward-facing footage even if the capsule flips.

With this successful trial run, the team plans additional testing on different horses. Ultimately, they hope to use the information they gather to seek funding for development of an equine-specific camera pill.

“From the engineering side, we can now look at good data,” Dr. Wahid explained. “Once we know more about the requirements, we can make it really customizable, a pill specific to the horse.”

This article was originally published in Practical Horseman’s October 2016 issue.

I hope you enjoyed reading about Misunderstood, Misused, & Misdiagnosed Disease #1: EPM. In that post I explained how some horse enthusiasts (trainers, owners, etc) have used this disease to e…

I hope you enjoyed reading about Misunderstood, Misused, & Misdiagnosed Disease #1: EPM. In that post I explained how some horse enthusiasts (trainers, owners, etc) have used this disease to e…

Source: Misunderstood, Misused, & Misdiagnosed Disease #2: Lyme Disease

For the past 6 weeks, my horse has been receiving Ozonetherapy to aid in his chronic back leg related issues- dermatitis (“scratches”), previous DDFT tendon laceration, a history of Lymphingitis, and the residual scar tissue from his DDFT injury. Due to his age (27), he lacks proper circulation in his hind end which does not help him fight his pastern dermatitis.

According to the American Academy of Ozonetherapy, Ozonetherapy is described as;

“Ozonotherapy is the use of medical grade ozone, a highly reactive form of pure oxygen, to create a curative response in the body. The body has the potential to renew and regenerate itself. When it becomes sick it is because this potential has been blocked. The reactive properties of ozone stimulate the body to remove many of these impediments thus allowing the body to do what it does best – heal itself.”

“Ozonotherapy has been and continues to be used in European clinics and hospitals for over fifty years. It was even used here in the United States in a limited capacity in the early part of the 20th century. There are professional medical ozonotherapy societies in over ten countries worldwide. Recently, the International Scientific Committee on Ozonotherapy (ISCO3) was formed to help establish standardized scientific principles for ozonotherapy. The president of the AAO, Frank Shallenberger, MD is a founding member of the ISCO3.”

“Ozonotherapy was introduced into the United States in the early 80’s, and has been increasingly used in recent decades. It has been found useful in various diseases;

After doing research and speaking to one of my good friends, we determined that Chance’s flare up of Lymphingitis, after almost 3 years of not a single issue, could possibly be caused by his immune system’s response to Ozonetherapy. Let me explain.

Chance suffers from persistent Pastern dermatitis (“scratches”) since I purchased him in 2000. I have tried everything- antibiotics, every cream and ointment and spray for scratches, diaper rash ointment, iodine and vaseline mix, Swat, laser treatments, scrubs and shampoos, shaving the area, wrapping the area, light therapy…you name it, I have tried it. So, when we began Ozonetherapy to help break down the left over scar tissue from his old DDFT injury, I noticed that his scratches were drying up and falling off. We continued administering the Ozonetherapy once a week for about 6 weeks. The improvement was dramatic!

However, one day Chance woke up with severe swelling in his left hind leg and obviously, he had difficulty walking. He received Prevacox and was stall bound for 24 hours. The vet was called and she arranged to come out the following day. The next morning, Chance’s left leg was still huge and he was having trouble putting weight on it. I did the typical leg treatments- icing, wrapping. The swelling remained. I tried to get him out of his stall to cold hose his leg and give him a bath but he would not budge. He was sweaty and breathing heavily and intermittently shivering. So, I gave him an alcohol and water sponge bath and continued to ice his back legs. I sat with him for 4 hours waiting for the vet to arrive. He had a fever and wasn’t interested in eating and his gut sounds were not as audible. He was drinking, going to the bathroom, and engaging with me. I debated giving him Banamine but did not want it to mask anything when the vet did arrive.

The vet arrived, gave him a shot of Banamine and an antihistamine and confirmed that Chance had a fever of 102 degrees and had Lymphingitis. There was no visible abrasion, puncture, or lump… I asked the vet to do x-rays to ensure that he did not have a break in his leg. The x-rays confirmed that there was no break. The vet suggested a regiment of antibiotics, steroids (I really am against using steroids due to the short-term and long-term side effects but in this case, I would try anything to make sure he was comfortable) , prevacox, and a antacid to protect Chance from stomach related issues from the medications. It was also advised to continue to cold hose or ice and keep his legs wrapped and Chance stall bound.

The following day, Chance’s legs were still swollen but his fever had broken. The vet called to say that the CBC had come back and that his WBC was about 14,00o. She suggested that we stop the steroids and do the antibiotic 2x a day and add in Banamine. I asked her if she could order Baytril (a strong antibiotic that Chance has responded well to in the past) just in case. And that is what we did.

Being as Chance had such a strong reaction to whatever it was, I did some thinking, discussing, and researching…first and foremost, why did Chance have such an extreme flare up of Lymphingitis when he was the healthiest he has ever been? And especially since he had not had a flare up in 3+ years…plus, his scratches were getting better not worse. The Ozonetherapy boosted his immune system and should provide him with a stronger defense against bacteria, virus’, etc. So why exactly was he having a flare up? And that is when it hit me!

In the past when Chance began his regiment of Transfer Factor (an all natural immune booster), he broke out in hives. The vet had come out and she felt it was due to the Transfer Factor causing his immune system to become “too strong” and so it began fighting without there being anything to fight, thus the hives. My theory- Chance started the Ozonetherapy and his body began to fight off the scratches by boosting his immune system. As the treatments continued, his immune system began to attack the scratches tenfold. This resulted in his Lymphatic system to respond, his WBC to increase, and his body temperature to spike. Makes sense…but what can I do to ensure this is not going to happen again?

My friend suggested attacking the antibiotic resistant bacteria by out smarting them…okay, that seems simple enough…we researched the optimal enviroments for the 3 types of bacteria present where Chance’s scratches are (shown in the results of a past skin scape test). The bacteria – E. Coli, pseudomonas aeruginosa and providencia Rettgeri. The literature stated that PA was commonly found in individuals with diabetes…diabetes…SUGAR! How much sugar was in Chance’s feed? I looked and Nutrina Safe Choice Senior feed is low in sugar…so that is not it. What else can we find out? The optimal temperature for all three bacteria is around 37 degrees celsius (or 98.6 degrees fahrenheit), with a pH of 7.0, and a wet environment. Okay, so, a pH of 7.0 is a neutral. Which means if the external enviroment (the hind legs)pH is thrown off, either to an acidic or alkaline pH, the bacteria will not have the optimal enviroment to continue growing and multiplying. How can I change the pH?

Vinegar! An antimicrobial and a 5% acetic acid! And…vinegar is shown to help kill mycobacteria such as drug-resistant tuberculosis and an effective way to clean produce; it is considered the fastest, safest, and more effective than the use of antibacterial soap. Legend even says that in France during the Black Plague, four thieves were able to rob the homes of those sick with the plague and not become infected. They were said to have purchased a potion made of garlic soaked in vinegar which protected them. Variants of the recipe, now called “Four Thieves Vinegar” has continued to be passed down and used for hundreds of years (Hunter, R., 1894).

I went to the store, purchased distilled vinegar and a spray bottle and headed to the farm. I cleaned his scratches and sprayed the infected areas with vinegar. I am excited to see whether our hypothesis is correct or not…I will keep you posted!

References & Information

Effect of pH on Drug Resistent Bacteriaijs-43-1-174

What does my horse’s CBC mean?

Your horse comes in from being outside and is barely able to move. His legs are swollen, he has a fever, is sensitive to the touch, and has a loss of appetite. He has chills- intermittently shaking. He wont touch his hay, his eyes are dull, and he looks depressed and tired. You call the vet and they run hundreds of dollars worth of tests- CBC, x-ray his legs to ensure there is no fracture; they diagnose him with Lymphingitis. You begin a course of antibiotics. You cold hose. You give him Banamine. Your wrap his legs while he is on stall rest. A week later, the swelling has subsided, his fever has dissipated, and his appetite is back.

You get a text saying that your horse “ran away” when he had been let out earlier that day. But when you get to the barn, you notice when he turns he looks like his hind end is falling out from under him..remember when you were little and someone would kick into the back of your knees and your legs would buckle? That is what it looks like. So you watch him. You are holding your breath, hoping he is just weak from stall rest. You decide, based on the vet’s recommendation, to let him stay outside for the evening. You take extra measures- leaving his stall open, with the light on, wrapping his legs, etc- and go home. Every time your mind goes to “what if..”, you reassure yourself that your horse is going to be okay and that you’re following the vet’s advice and after all, your horse had been running around earlier that day.

The next morning your horse comes inside and it takes him an hour to walk from the paddock to his stall. All four legs are swollen. He has a fever (101.5). He is covered in sweat. He won’t touch his food. He has scrapes all over his body and looks like he fell. You call the vet- again- and they come out to look at him. They note his back sensitivity, his fever, the swelling at his joints (especially the front). They note that his Lymphingitis seems to have come back. The vet draws blood to check for Lyme. They start him on SMZs and Prevacox. You once again wrap his legs, ice his joints, give him a sponge bath with alcohol and cool water to bring down his fever. You brush him, change his water, put extra fans directed at his stall. You put down extra shavings. And you watch him.

A few days go by and you get a call saying that your horse has tested positive for Lyme…and while your heart sinks, you are also relieved that there is an explanation for your horse’s recent symptoms. You plan to begin antibiotics and pretty much not breathe for the next 30+ days while your horse is pumped with antibiotics. You pray that he doesn’t colic. You pray that you have caught Lymes in time. You pray that the damage is reversible. You research everything you can on the disease. And you sit and wait….

Below are resources on Lyme Disease in horses- treatments, symptoms, the course of the disease, and the prognosis.

Lyme Disease in Horses | TheHorse.com

Lyme Disease, testing and treatment considerations | Best Horse Practices

Microsoft Word – Lyme Multiplex testing for horses at Cornell_2-12-14 –